We’re a day early (well, not so much over in Asia), but today I thought I’d like to touch on the Battle of the Philippines Sea that took place tomorrow and the day after, seventy-three years ago.

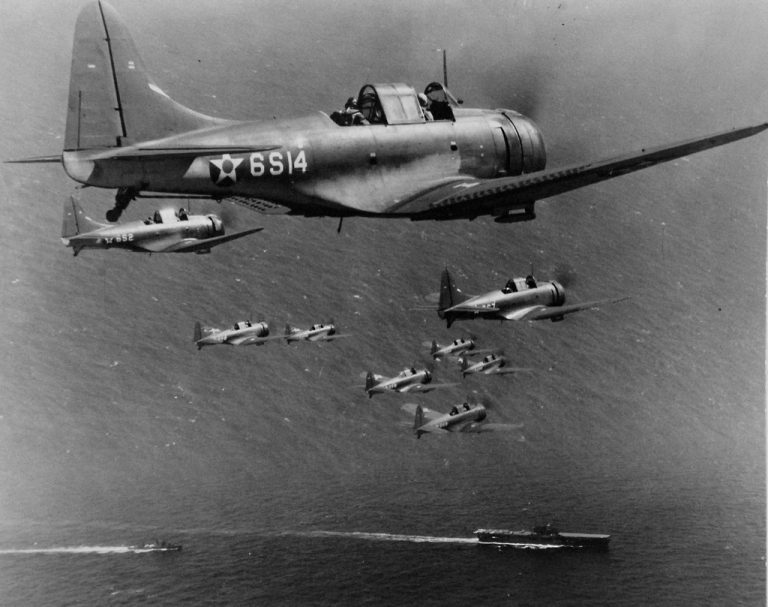

Colloquially known as the “Marianas Turkey Shoot,” this, more so than Midway, was what dealt the IJN a killing blow. On the first day, the USN destroyed no less than 358 Japanese planes (in a post-war account in 1945 – you’ll find numbers varying here and there due to reporting discrepancies) at a loss of 33. Taking into account the second day’s events, Japan would lose three carriers and more than 600 carrier and land-based aircraft.

The damage done to the IJN was irrecoverable. In two days Japan had lost its fleet air elements, depleted its pilots and reserve aircraft, and lost capitals ships that it could not afford to lose. While Japanese media downplayed the impact, the evidence speaks for itself when four months later, the once capable carrier task force was sent out as bait during the Leyte Gulf operation.

What went wrong?

Well, for starters, I did ask Sune – citizen of Japan, (literal) daughter of samurais, and our residential IJN expert. She had this to say.

OZAWA DID NOTHING WRONG

While tongue in cheek, Sune’s assessment of the IJN boiled down to the following perspectives. It was a bit like a reverse-Midway in that this time, the IJN had several advantages that the US enjoyed. It had access to land-based aircraft. Land-bases means that the Japanese planes can strike, land at a Japanese base, refuel and rearm, and go in for another strike. The carrier force, while diminished, was in capable hands given Jisaburo Ozawa’s command. The winds were in favor of the Japanese.

Like Midway, this was a battle the IJN had to win. The Truk and Marianas “line” was Japan’s final line of defense. The reason why we went after Saipan was that through Saipan, we can launch strategic bombers at the Japanese home islands. Taking the Marianas area renders the entire Japanese force vulnerable, and the IJN was well aware of this. Not to mention, the recent string of losses were some of the first losses of territory that were previously in Japanese hands.

At the time of the Battle of the Philippines Sea, Saipan has been in American hands for only a few days. We were every bit aware that the Japanese wanted it back, and given the strong endurance of the lighter IJN (and IJA) planes, a battle was expected. Again, similarly to Yamamoto’s original thinking, Nimitz also sent a message to the fleet on the eve of battle. It read:

The officers and men of the Fleet have the confidence of the naval service and their country on the eve of a possible major surface engagement with the enemy. We count on you for a decisive victory.

In a very curious parallel to Midway, we need to remember: Admiral Mitscher was supposed to be bombing Guam. Much like how Nagumo was ordered to both destroy Midway’s garrison and the US surface fleet, Spruance was meant to reinforce and protect the Marianas invasion fleet. To that end, he was to take the opportunity to hit Japanese airfields on positions such as Guam if he could.

(I didn’t find any evidence of Nimitz telling him to attack the islands. However, Spruance is not a passive commander – so it’s entirely plausible that he’d take advantage of the opportunity if it comes up)

The Japanese, on the other hand, saw the destruction of the US carrier force as their primary goal. Here again would be an excellent parallel – just as Nimitz ordered Spruance to inflict as much attrition damage as possible, here, too, did the GHQ order Ozawa to destroy decisively the Fast Carrier Task Force.

Indeed. Spruance and Mitscher did order strikes against Guam on the morning of the 19th. However, here is where things went very differently.

First, we immediately recalled the island strike groups over Guam upon finding out the massive amount of Japanese plane readying up and taking off. Both Spruance and Mitscher were at Midway. They know exactly what happens to carriers if an enemy attack can catch them unprepared. The important thing was to get fighters in the air to interdict enemy planes.

Failing to do so would make the respotting (aircraft has to be “spotted” forward on the flight decks so the after portions of the flight deck can be free to recover incoming planes) highly dangerous since the planes on the decks themselves can be damaged and destroyed (to say nothing of the carriers themselves).

What’s more, as the fighters took off, the torpedo bombers and dive bombers were sent off in the opposite direction – just in case something was to slip through. This minimized the dangers of catastrophic explosions – the likes of which that took out the Akagi during Midway.

Like Midway, Ozawa threw group after group of aircraft at the US fleet. Totaling nine waves in all, some of which involved large groups of forty to fifty planes. On the US side? All the US carriers did was to cycle through and refuel/rearm the fighters. Terse excitement was in the air as the US forces realized upon seeing the waves and waves of attacks that this was the big one – this was it!

From about 10 to 3 the IJN attacked all day. They didn’t hit a single US carrier, and the only ship damaged was a battleship (the South Dakota). US submarines found and hit the Shokaku and Taihou, and by evening the US launched 240 planes to hit the rest of the Japanese fleet. Hiyou was sank nearly instantly, and the remaining carriers – Zuikaku, Junyou, and Chiyoda – were damaged.

That night, Admiral Toyoda ordered Ozawa to retreat. The Battle of the Philippines Sea was over. The US lost far more planes (80 in all) as a result of ditching in the water on that last attack wave than the Japanese shot down.

What happened? In no particular order…

The Hellcat happened, for one. The US had better planes this time around. The Wildcat could give the Zero a good fight (and I would actually argue that it’s better than what most people give her credit for).

Two. The US were not the inexperienced green recruits of the Hornet flying at Midway. These were veteran pilots – some with thousands of hours of flight experience and confirmed kills – flying a plane that outclassed the Zero. The Japanese had some veterans from Midway (and indeed, many would continue to survive) but the bulk of their trained pilots were shot down in this battle. Here, they were the inexperienced ones in comparison.

Three. Radar happened. The USN saw the IJN come from hundreds of miles away. Like Midway, this prompted the US carrier commanders to act.

Four. The US had better battle doctrines. Whether it’s target prioritization or layering AA fire with the escorting fleet elements or intercepting enemy air, the US held a tactical advantage over the IJN in this battle.

At this point, it might be tempted to ask. The USN was able to overcome many IJN advantages at Midway and score a miraculous victory. Was there any way for the IJN to have done the same – taking out one or more of the US fast carriers to make this battle more even?

The answer is yes. Anything is possible. However, and this brings my piece to an end here – I think it would be extremely unlikely. Leadership and discipline is the final advantage that the US had, and this advantage was paramount. The US was blessed by the twin benefits of having good officers on the field – individuals such as Mac McCampbell of the Air Group 15 – and steady fleet commanders such as Spruance.

These guys knew what they were doing and were focused on their task. The fact that the US CAP didn’t run off to chase after IJN torpedo bombers and the IJN dealing virtually no damage to the US carriers is proof of that.

For something like Midway to happen, you need luck, of course, but you also need to capitalize on any temporary advantages as well as punishing the enemy for their mistakes. The USN at Midway had all three. The IJN at the Battle of the Philippines Sea had little of the first, unsure of the second, and definitely had little to exploit when it comes to US mistakes.

In fact. I think it’s impressive that something like 130 IJN carrier planes managed to make it home out of the near-400 that sortied. The losses of the carriers (and many of these planes) after? Well, that’s incompetence, plain and simple, but one could hardly fault the pilots for that.

See you next time – and, cheer up, Zuizu. You’re still my favorite Japanese CV girl. 🙂