Sune’s earlier comment on the bigger picture is a good note to lead into today’s piece, which will be concluding our three-parter on the Battle of Midway.

I want to make two major notes here in today’s piece. One is that I think we had the advantage in orders. Two is that – as you’ll see in a bit – it was a hard-won victory.

To begin, I think America’s advantage in the Battle of Midway, all else considered, was a stroke of good fortune in the form of having the right commanding officers.

While Sune was largely right to criticize Yamamoto (he is, after all, the commanding officer), I think I’d like to say that Yamamoto had the right general idea. Famous for wanting to end the war quickly, he needed that decisive battle, he needed to lure out the US carriers, and he needed to do it without doing it close to Hawaii.

From the Japanese perspective, GHQ was absolutely glowing with cheer. Even Hitler sent a congratulations to Tokyo, stating that “After this new defeat, the US warships will hardly dare to face the Japanese fleet again. Any US warship which accepts action against the Japanese naval forces is as good as lost!”

Why did no one speak up against Yamamoto’s overly complex plan? I think it’s safe to say, nobody wanted to. To the Japanese, victory felt like it was near. Taking into context of the times, the Japanese assumed that we were nearly beaten and ready to surrender. With that assumption, then, their planning makes sense. Their mistake was not accurately assessing whether or not said assumption was correct. Let me share a funny little story aboard the Yamato that illustrates this point.

In the celebration of the Coral Sea battle, the cook messed up the fish. Heijiro Omi, steward of Yamamoto, saw that the tai, a fish that was cooked from head to tail, was broiled in miso rather than salt. There’s an expression in Japanese – to put miso on something – is a metaphor for making a mess. This was an ill portent, but Yamamoto himself ignored this. He instead proceeded to get drunk with the other officers.

An anecdote, but I think it illustrates the point well. Japan got a little careless. Yamamoto should have considered the portents more – especially about what would happen if the Americans did not play according to plan.

Simply put, Yamamoto made a number of key assumptions that he did not really follow through to confirm, nor did he communicate well what was to be expected if an encounter was to occur. Had he kept it simple – destroy the US airgroup at Midway, clear the way for the invasion force – or, alternatively, – destroy the US fleet – the execution would have been much simpler.

As it stands? Nobody had any idea what Nagumo was supposed to do when the US carriers showed up. This part was never made clear to anyone, and I think Nagumo did his best to follow his orders through. When he had no confirmation that the US carriers were near, he simply bombed Midway as ordered. After he found the US carriers, he attacked the carriers – as ordered.

Contrast this with Nimitz, who had a much simpler plan in mind. Meet the Japanese at Midway and inflict heavy damage. The navy codebreakers gave him an important edge here as he knew that the Japanese were after Midway. He put the right number of pickets – submarines, flying boats, and scout aircraft – in his Midway task force, and he gave Fletcher and Spruance very simple orders.

“Inflict as much damage as possible by using strong attrition tactics. Apply the principle of calculated risk which means avoiding exposing your forces to attack by the superior enemy forces without good prospect of inflicting greater damage to the enemy.”

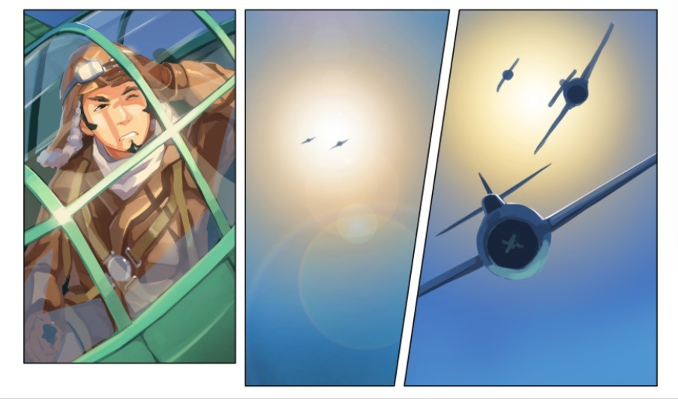

It goes without saying that this was far easier to adhere to than Nagumo’s orders. Yet even so, the Japanese held most of the tactical advantage. The four carriers of the Kidou butai has more advanced aircraft, more aircraft (if we purely count the CV aircraft), better fighters, better torpedo bombers, and I would contend (based on combat experience and hours of flight) more experienced air crew overall.

Where we had the edge, if you’re to believe this America, was morale.

The Japanese strike force’s morale was high. I would say they were impetuous, and we have plenty of evidence for this ranging from records of non-fighters impromptuly dropping ordnance to dogfight the slow USN fighters to the massive lemming train (apologies, but that’s basically accurate in describing the CAP above the Japanese CVs when we hit) trying to gun down more planes for personal glory. In their eagerness to cement this victory, they opened themselves up to attack.

On the US side? Morale was high. I’ve gone through countless anecdotes and recollections, and the entire fleet wanted to slap-the-Japs and give them a solid thrashing. Everyone knew the odds. They knew that the enemy had more carriers and more planes. Admiral Fletcher just told them that.

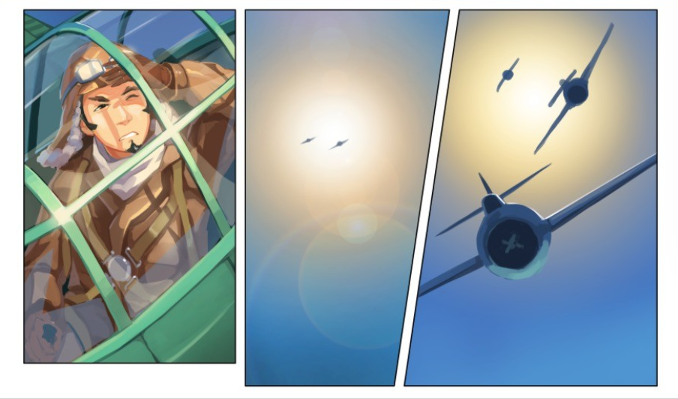

Yet there was no fear. Just excitement. Nobody know how, but the information spread like wildfire. At long last here was a chance to fight back. In the words of the leader of Torpedo 8 – the squadron from Hornet that didn’t come home: “If there is only one plane left to make a final run in, I want that man to go in and get a hit.”

Just a word to let you know I feel we are all ready. We have had a very short time to train, and we have worked under the most severe difficulties. But we have truly done the best humanly possible. I actually believe that under these conditions we are the best in the world. My greatest hope is that we encounter a favorable tactical situation, but if we don’t and worst comes to worst, I want each of us to do his utmost to destroy our enemies. If there is only one plane left to make the final run-in, I want that man to go in and get a hit. May God be with us all. Good luck, happy landings, and give ‘em hell.

“We will go in, we don’t turn back. We will attack. Good luck!”

They knew that the planes were obsolete and that the equipment was poor, but they went in anyways. They were given orders and they were determined to follow through. Such was the mind of everyone involved in the Midway attack force. This is the definition of heroism.

As it stands? The lone survivor, George “Tex” Gay, watched his squadron leader, then the rest of his squad go down. Then his plane was shot down as well. All 15 TBDs of Torpedo 8 were shot down. Despite fighting to the last man, no one scored a hit.

What Torpedo 8 went through was no different than every other US air group that tried to do their duty. Let’s run down the list.

Wave One:

6 TBF Avenger Torpedo Bombers from Midway. 1 survived. No hits.

4 Army Marauders from Midway. 2 survived. No hits.

Wave Two:

15 B-17 Flying Fortresses attack. No hits.

Wave Three:

16 USMC Dauntlesses from Midway. 8 survived. No hits.

Wave Four:

12 USMC SB2U Vindicators from Midway. 7 survived. No hits.

Wave Five:

15 TBDs (VT-8) from Hornet. 0 survived. No hits.

10 Wildcats (VF-8) from Hornet. Could not find target & ran out of fuel. 0 survived. No hits.

16 SBDs (VB-8) from Hornet. Could not find target. 13 survived (3 were lost due to fuel). No hits.

16 SBD (VS-8) from Hornet. Could not find target. All returned to carrier with bomb still attached. No hits.

Wave Six:

15 TBDs (VT-6) from Enterprise. 5 survived. No hits.

10 Wildcats (VF-6) from Enterprise. Circled above Kidou Butai waiting for signal from VT-6 or other air groups. No signal was received. 10 survived to return to Enterprise. No hits.

Wave Seven:

12 TBDs (VT-3) from Yorktown. 0 survived. No hits.

6 Wildcats (VF-3) from Yorktown. 5 (4) survived. No hits.

… let’s hold on for a second and look at this. By the numbers, how were we doing?

“Terrible” is putting it nicely, don’t you think?

I bring the numbers up to emphasize that Midway was a hard-earned victory. Different historians have different perspectives on just how much each individual airgroup’s sacrifice contributed to the victory at large. Certainly they drew off the fires from the Zeros and forced the Zeros to go off position. They definitely kept Nagumo off balance and delayed any launches of attack groups. Yes, at the end of the day, they ate up bullets and cannon shells from the opposing Zeros.

But honestly ask yourself. Does this – total losses of multiple squadrons – look like winning to you?

Even the SBDs that showed up immediately after took heavy losses. VS-6 came with 18 SBDs and left with 10. VB-6 showed up with 15 and left with 7. Yorktown’s VB-3 fared better, only losing 2 out of 17, but Max Leslie showed up with a quarter of his bombs missing. VS-5, the other Yorktown bomber group, was held back in reserve.

Fateful Five Minutes, indeed.

As it stands, the entire SBD force dogpiled Kaga. What made the difference in this first round was that VB-6’s Best took initiative to split off and go for Akagi instead, and a single lucky hit was scored that took her down for good. Meanwhile, Leslie’s group ripped apart Soryu, and the rest, as we say, became history.

Ask yourself what would have happened if the Yorktown and Enterprise SBDs showed up piecemeal like the others? Let’s not forget that they were without fighter cover.

What would have happened if Best didn’t veer off but went after Kaga instead? How would a 2 for 2 counterattack looked like for the US?

If we’re going to be objective, we can find plenty of faults with the way we fought. Let’s remember what we didn’t do right, and be thankful for the things that we did do right.

Part of the reason for why I love history so much is that while it may be incredible tales of valor to us, never forget that sometimes before – in this case, before we were even born – these were real men flying real planes fighting in a war that was very real.

I hope now you understand why I think Midway’s “Incredible Victory” is well deserved.