Hi! Tautog here. Yes, Morgane’s actually put me in charge of the rest of the site, at least for the weekend while she’s busy taking a break from a lot of overtime at work.

Given it’s November, I thought I’d provide some historical context on how the battles at Guadalcanal took place. See! We talk a lot about how these were some of the most amazing and unusual naval battles during WW2, but I think we should understand just what was going on in the minds of our commanders (and the Japanese).

The general situation at Guadalcanal is not unfavorable.

Nimitz, Oct. 30th, 1942.

Let’s recap a bit about what has happened since. Coral Sea. Midway. Eastern Solomons. Santa Cruz. We’ve had four big carrier battles in a very short amount time, and we were beginning to see the light at the end of the tunnel. US fighter pilots were getting adept at fighting the Zero in the air. US CV officers were learning how best to control and direct their air groups. Fighter cover is improving. Aerial recon is improving. AA gunners were improving (the new AA guns do help!) and the general situation is doing better.

To put it simply, we’re learning. The Japanese were too, but they were less quick. While we did just lose the Hornet, Japan is stuck consolidating forces at Truk. Furthermore, they were unable to dislodge the marines fighting around Guadalcanal – the Savo Island victory, ironically, removed Japanese focus from their losses there. While official Japanese media was wildly enthusiastic (Santa Cruz was chalked up as “three US carriers and one battleship sunk,” haha) the actual military’s outlook was somewhat mixed despite the Emperor’s encouragement below.

The Combined Fleet is at present striking heavy blows at the enemy Fleet in the South Pacific Ocean. We are deeply gratified. I charge each of you to exert yourselves to the utmost in all things toward this critical turning point in the war.

On one hand, Nagumo and Kusaka estimated that a good number of carriers (Ugaki calculates 4, Nagumo is more conservative and assigned it 3) are sunk. Midway has been avenged! Tokyo has been avenged! (The Japanese were well aware that the Hornet would have made a fine prize) Tennou-heika-banzai!

On the other hand, Japan has once again stretched themselves dangerously thin. Post-war pro-navy anti-army narratives tend to pin the failure on the Imperial Army, who failed three times over the last month to retake Guadalcanal. However, it must be pointed out that the Emperor himself also had significant influence in the campaigns that followed. For instance, within the same dispatch as above, here is a second part.

Regarding the struggle for Guadalcanal. It is a place where a bitter fight is being waged between forces of Japan and the United States. It is an important base for the Imperial Navy and I hope that the island will be recovered by our forces as soon as possible.

Emphasis on “as soon as possible.” This demand was not at all unreasonable, as the Imperial Army has been bleeding men left and right. Implicitly, a huge amount of pressure was thusly placed on the navy to deliver greater and greater results. This is where the Imperial Navy starts to bleed as well. Japan has not been able to trade aircraft with the Americans very well. One 70 plus plane loss like the Eastern Solomons or Midway battle might be absorbable, but Santa Cruz brought another (some sources count up to 90, others at least 69) staggering loss to Japan’s naval air.

In other words, the writing was on the wall. The USN is starting to learn, as I’ve mentioned up there, and Japan’s losing far too many planes and pilots at this point. Something has to be done, and Japan decided to seize the initiative.

Thus, the better question to ask is why wouldn’t Japan risk a naval assault on US forces after Santa Cruz? There is no way Japan would not try to force a naval action to knock the US navy out of the game. They had to. The army was running out of supplies. The Americans were bringing more and more troops in by the day. GHQ counted on the American carriers being out of action – even if the carriers weren’t sunk, they surely could not stop the Japanese from advancing further. The IJN brought what transports they could spare, and sent a large convoy forward. In total, during the days before the actual battle, sixty-five destroyer loads of troops were dropped on the island.

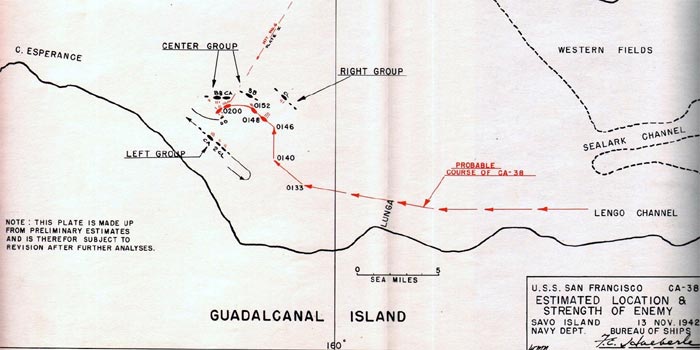

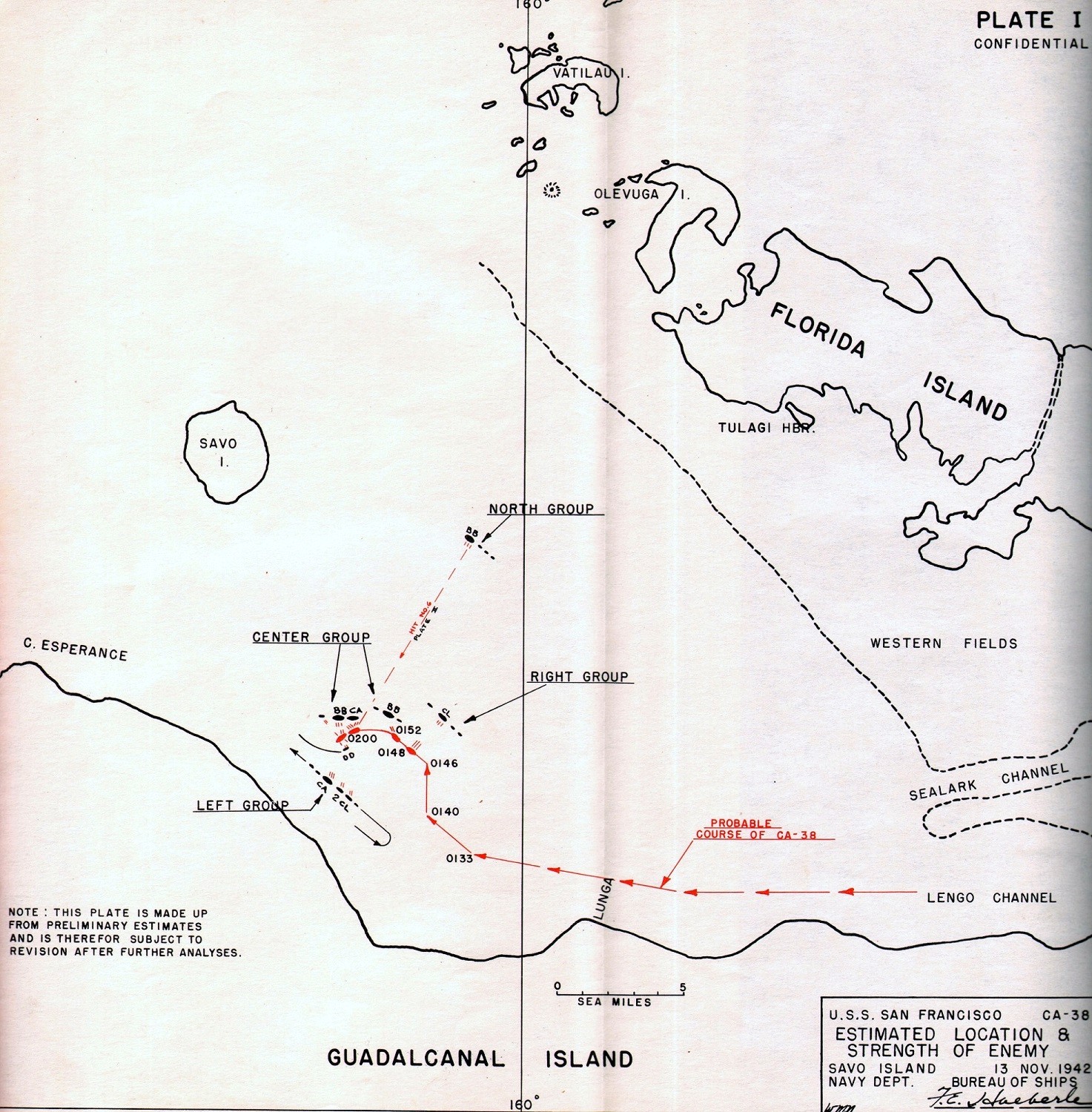

To catch any American reinforcements off-guard, Yamamoto sent out a a raiding force. This is Hiroaki Abe’s group with two BBs, 1 CL, and 11 DDs. This force had a simple mission. Hit Henderson field. Neutralize it. Let the Imperial Army reinforce Guadalcanal.

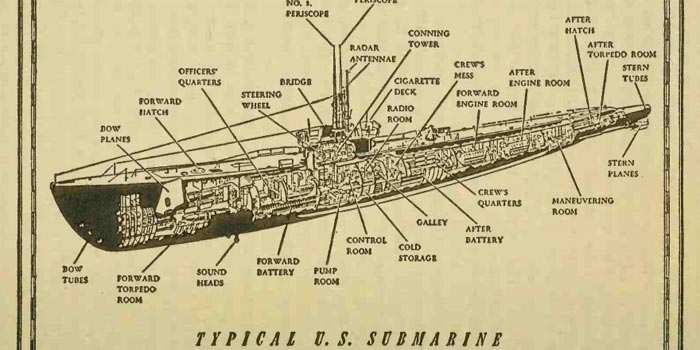

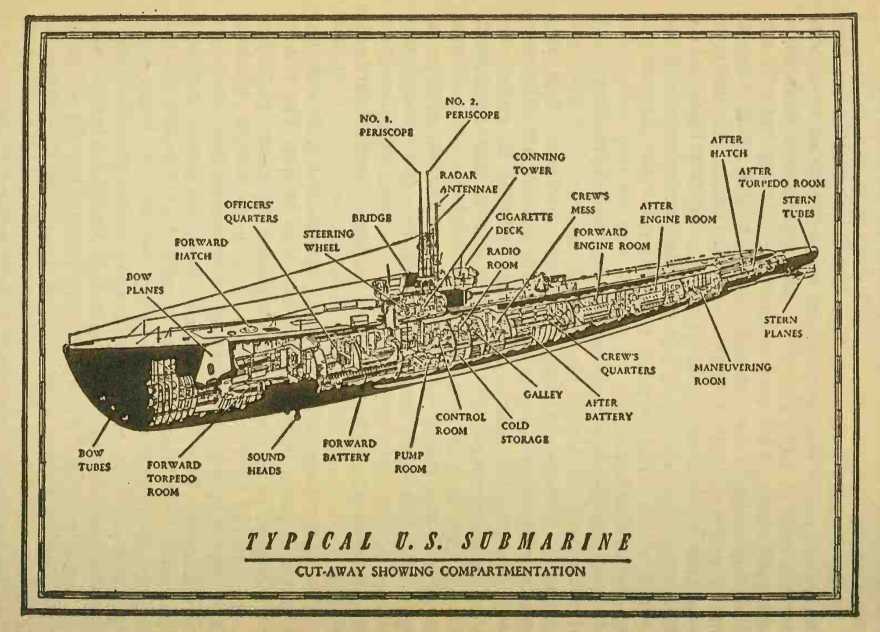

Here’s where the plan went awry. Our submarines, twenty-four in all, saw them coming from a (few hundred) mile away.* What’s more, Halsey has already correctly deduced that the Japanese would try this move, and called in Kinkaid’s TF 16. Sure, Enterprise was still under repairs, but the battleships and the DDs on our side should be more than sufficient. After all, our goal is to destroy enemy naval units and interdict Japanese reinforcements.

Meanwhile, we’ve got our own transports on the way. The primary combatants of the 1st naval battle of Guadalcanal actually came from the escorting ships of two transport convoys. The first group, Admiral Scott’s Atlanta and her DD escorts, were escorting attack cargo ships. These, such as the USS Libra, were pretty heavily armed for transports and could provide some fire support if needed. The second group, Admiral Callaghan’s cruisers and destroyers, were escorting transports.

Imagine yourself in Callaghan’s shoes. You know that this was probably one of the most important sites of the entire Pacific War. You know, for a fact, that the Japanese were coming with battleships. On the 10th of November, your superior basically told you to expect a heavy Japanese attack coming your way.

Originally, if things went well, the transports would drop in quietly and leave as soon as possible. That didn’t happen, as the Japanese scouts were very good, forcing Callaghan to immediately unload. Submarine, aircraft, and other intelligence basically confirm the presence of Abe’s task force – the one with the two BB – coming this way. Furthermore, in the same day, carriers were also sighted.

The intent here is clear. The Japanese is going to attack the American transports and try to cut off supplies. If the transports are sunk, it’ll be a major blow to US forces. But the real prize is Henderson airfield, which the Japanese are almost certainly going for – especially with that large task force they’ve sent.

You have a couple of cruisers and a bunch of small ships.

There is literally nothing else. No reinforcements will be coming tonight. Meanwhile, you’re almost certain that they’re coming tonight.

So what do you do?

We’ll block’ em. Hard.

Puts Sanny’s profile quote in vol. 2 (“Yes, I know it’s suicide. But we’ve got to do it!”) in a new context, doesn’t it?

Callaghan was a good man. Quiet. Contemplative. He was well-liked by his crew (they affectionately called him Uncle Dan) and was known to be a capable officer. Almost everyone who knew him comments that his faith plays a big part in his actions and interactions, and he carries himself with a sort of dignity not unlike heroes like Hector or Roland or, you know, any number of personages from ancient epics.

This is not to say that he made no errors. Plenty of errors were made on both ends. Some were avoidable. Others weren’t. But, I think given what we know of him, it’s clear that Callaghan went in with the intent of completing his mission.

Now, close to a hundred years later, I think we can all proudly tell the admiral, mission accomplished.

*Morgane’s editorial comment: Tautog is obviously very pro-submarines. While it is true that submarine scouting provided significant intel, it really is a massive team effort, from our submarines to our airplane scouts to intelligence agents embedded in various Japanese bases to literal eyeballs. 🙂