Seventy-five years ago, on this day, the war was still looking bleak for the Allies. U-boats rampaged through the Atlantic. The Red Army was being ground down by Hitler’s assault on the Soviet Union. Rommel was trying to break into Egypt.

And, because Pacific focuses on, well, the Pacific, let’s not forget how the IJN rampaged through the Asia-Pacific over the last six months. We know – though the public might not – that Coral Sea was something of a draw. Tensions are high. This next battle would prove to be critical.

From the Japanese perspective, if they can draw out the US fleet in a good engagement and destroy it, they’ve then got the war in the bag. If they can decapitate the US naval forces here, then American would surely sue for peace and in the process, pay off Japan’s magnificent gamble back in ’41.

From the American perspective? The stakes were high. Midway’s strategic position cannot be understated. Coral Sea threw the Japanese slightly off balance, but if Midway is lost – along with its carrier defenders – then Japan will have another six months of free reign in the Pacific. US carriers were under production, but no new carriers could be brought in until at least the end of 1942.

Plenty of people’s written on Midway before. Many prominent historians and well-learned scholars all gave their own opinions on what this battle is. I can give you a good reading list if you’d like. Popping over on the Midway Round Table for an excellent review of books.

However, as we gear up vol. 3 for print, here’s my perspective on Midway.

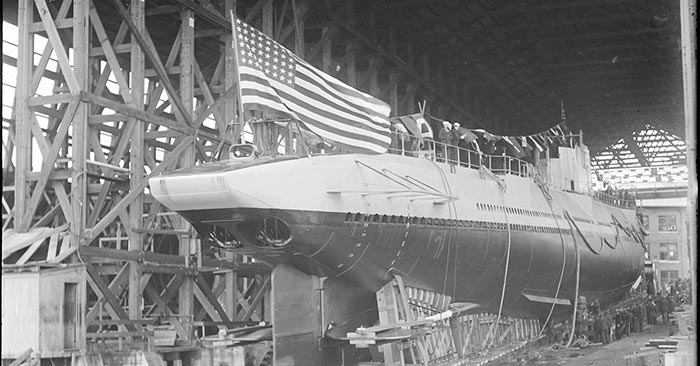

- The “Fateful Five Minutes” as told by Fuchida is not quite myth despite how hard people have tried to debunk him. The Japanese strike groups were very close to being able to launch an attack, and an additional twenty minutes may have been all that’s necessary. If one or two other things went less than optimal for the U.S. forces – e.g. the IJN backing off on Nautilus or one of the SBD groups changing course earlier or later – the Japanese should have been able to at least get an attack wave off before being attacked.

- For that matter, three of the four Japanese carriers were on fire within the span of about three to eight minutes. At that point even if Hiryu could have scored 2 for 2 it wouldn’t have been enough to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. In that sense I’d say the “five minutes” is very accurate. Whether or not Fuchida saw planes on the flight deck (there probably were fighters, just saying), the results showed for themselves.

- Walter Lord’s quote on Midway, ““They had no right to win, and yet they did, and in doing so they changed the course of the war,” is not inaccurate. Miracle might be a bit too strong, but I think it was certainly an incredible victory. A few examples:

- The IJN were hardened veterans. Nagumo’s been directing combined carrier operations for months. In contrast, Hornet was completely green. I’m not trying to discount the bravery or the competence of the American forces, but the Japanese navy were good and we acknowledged that.

- The US had no way of knowing whether or not the IJN would bring in 4, 5, or 6 carriers. Zuikaku and Shokaku may have been heavily damaged/suffered heavy air group losses, but it wasn’t certain that they would be out of the battle.

- Counting the air field at Midway, the US still barely had air parity. The numbers of planes in the air might be similar, but the US were operating a smattering of old aircraft. The F4F was barely a match for the A6M, let alone the F2As.

- Many great books – ranging from Dr. Symond’s Battle of Midway to Parshall & Tully’s Shattered Sword – point out various flaws in Japanese tactics of the day. Many errors and mistakes – such as inadequate scouting or poor fighter discipline – costed Japan the battle, but I think it’s worth mentioning that one should never assume that the enemy’ll be making these mistakes. I don’t think for a second that Gallagher and Best and McClusky and co. went into that battle thinking, “man, the Japanese’s surely going to get arrogant and make dumb mistakes.”

- The scope of the US victory – the destruction of all of Japan’s carriers – is extraordinary. McClusky and Leslie could not have coordinated that attack together. They could not have known ahead of time that the Japanese were in complete disarray. The attacks could have all gone into Kaga (and it did look like that was the case if it weren’t for a stroke of fortune on Best’s part) and Soryu. And so on and so forth.

You get the idea. As I said, miracle might – can, depending on your inclination – be too strong of a word. These were brave men who did their best to do the jobs they were given. Each went into the battle determined to perform the best he could offer. The rest is really left to the nebulous thing we call fate.

They could have missed. The others could have hit. They could have been shot down before they’d even get to the targets. They could have flew on and on and never even found the Japanese.

But, that is what real life is. Before 10 AM if we were watching the Pacific War we’d say that the Axis still held all the cards. By 11 AM? The tides have definitely changed.

It’s why Sima and I decided to caption our image for the third book the following way.

(We’ll talk lore in the next post)

A turn of fate; an unanticipated change in a sequence of events. I think Midway qualifies. After all, no one enters a battle with the assumption that they’d go in to lose. But I don’t think the US forces went into Midway thinking that they’d be able to score such an incredible victory.

In vol. 3, we’ll be discussing in much greater detail some of the conclusions that the team and I have reached. Until then, I’ll leave you with this quote – found scrawled on one of the US carriers in the day.

“Fortune Favors the Bold.”