Tautog here. I’ve been reading the comments and the mail and I’ve just realized that we haven’t talked about the very basics behind submarine design yet!

(Also, I’m a little tired of people arguing over which submarines are the best. The answer is of course the AMERICAN one, but you can make a good argument for many other countries’ creations, too!)

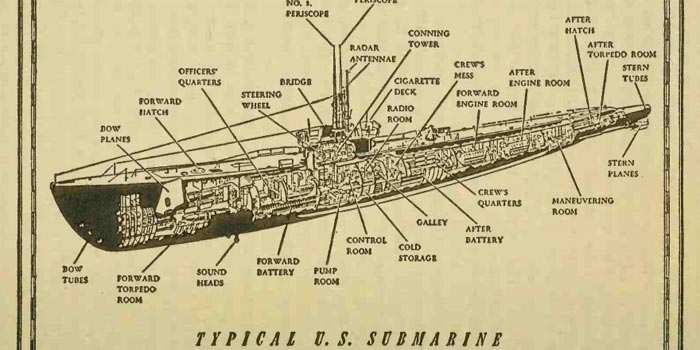

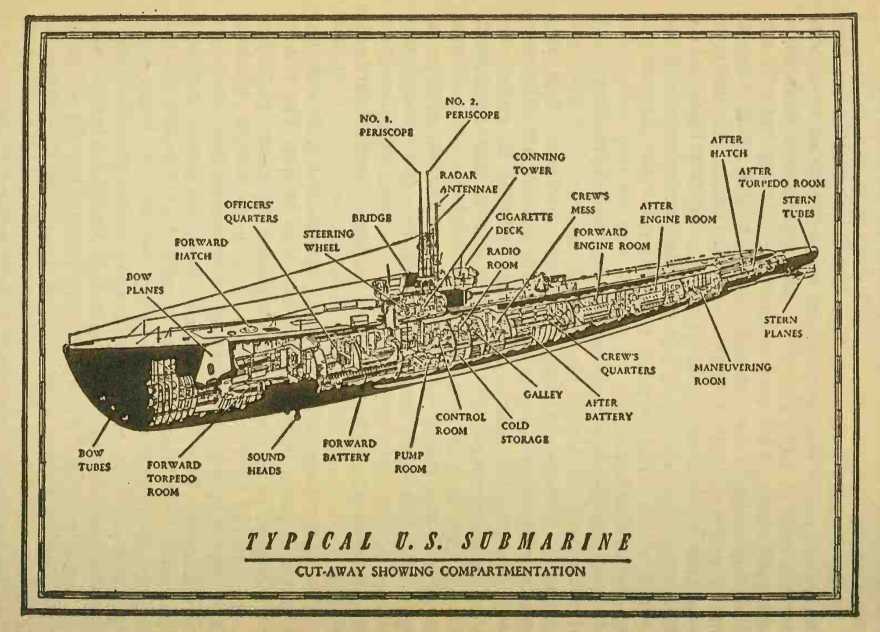

We’ve talked about the necessity of maintaining buoyancy before. However, I think it’d be good to just list off some general constraints that submarine designers are working under. So, in order, we’re going to be talking about the pressure hull, the materials of construction, the conning tower and periscope, and the powerplant. I’m also going to use the American ones during WW2 as an example – if you’re interested in the submarines of the other countries, I can grab one of our other girls to answer instead!

Since this is somewhat long, today we’re just going to talk about the hull of the submarine itself.

Okay. So. Pressure hull. This is the submarine itself. If you think about it, the submarine is literally just a giant metal floating box that needs to sink on demand, right? The pressure hull is the “wrapper” around all the machinery that goes into a submarine. Generally speaking, submarines are volume critical and not weight critical. This is because the submarine is completely enclosed, so any attempts to save weight will not necessarily result in smaller displacement, because the volume of the materials don’t change.

What this means is that weight saving measures can then translate into thicker pressure hulls. A thicker hull means that you can dive deeper. While it’s tempting to think that it would be good to make a submarine with a super-thick hull, eventually you hit a point where most of the weight comes from the hull itself. We call this being “weight critical.”

(If you have very heavy batteries or machinery, it might cause the same thing. Remember! You want to distribute the weight in a generally even way.)

This is not good, because it means special precautions must be carried out to make sure your submarine don’t sink like a rock. This issue is typically solved in modern submarines via a combination of very light but sturdy materials or careful placement of their inner machinery. Pre-WW2 US steel, by the way, was rated at a dive depth of about 250 feet. Today submarines obviously go a lot deeper than that!

Speaking of the hull, the shape of the submarine matters, too. In theory, a completely spherical object would be the best at resisting pressure. You actually see this principle at work in deep sea science exploration probes. However, a spherical submarine wouldn’t have very efficient use of space. As such, most submarines are in those long cylinders that you are familiar with today.

The important thing about cylinders isn’t that they’re cylinders, though, but rather, just what sort of a shape it is in. Generally, the designer have to keep in mind the overall surface to volume ratio, since higher surface area naturally causes more drag, which makes the submarine less agile. However, longer submarines could also fit in more powerful machinery. So in cases like the modern day Los Angeles class submarines, it actually worked out to be positive overall.

Anyways. Generally, there are three types of submarine hulls during WW2 times.

- Single hull: All of the tankage (the ballast tank; what controls the buoyancy of the submarine) is found in one single “shell.” It’s easier to build this type of submarine, and it has the least amount of surface area, so it is stealthy and fast. The downside is that with the tankage being inside the sub, you have a lot less space to fit in machinery. The US started out building single hull submarines, then went away from it quickly enough. It isn’t until modern day nuclear subs that we see the single hull submarine come back again.

- Double hulls: It’s as the name suggests. A floodable second hull encases the pressure hull, and reserve buoyancy is provided in the tanks located between the pressure hull and the case. The advantage here was that the submarines were bigger, they ran more efficiently on the surface (because of their larger freeboard, which improved seaworthiness), and they generally have greater range (owning again, to their greater size). Some think that the extra layer of “armor” makes it tougher against the lightweight submarine-killing torpedoes, but others don’t think so. In either case, the downside was that the double hull was technically challenging to build, and it dove very, very slowly. While it was pretty commonly used by many European countries around WW1 and inter-war eras (including the Surcouf, teehee), today only the Soviets (Russians) really stick to the double hull design.

- Then we have the compromise, or what is called the saddle tank design. Here, you have tanks mounted externally on a single hull submarine. This allows for much better compartmentalization and habitability since you’re carrying all that water outside, and the extra tanks actually allowed for a measure of stability due to the greater contact area between the submarine and the water. The downside? It had significant underwater drag, and it dove somewhat slowly as well.

So, yeah. I’ll probably go over some notable submarine examples in the next piece. In any case, I feel like it’s just something people should know about. Submarines are pretty neat, after all!

See ya next time.