Note: This was posted yesterday, but apparently stuff didn’t sync, so I’ll probably have something up today as well.

First things first. The website’s experiencing troubles (again) over the weekend. What I can say with some honest confidence is that it goes down due to any number of things ranging from attacks to too much server traffic to general shenanigans.

Sorry, folks, but it’s what it is. We’re doing our best.

Thank you for the random questions. Zero’s actually working on the video-related stuff now.

Right now, it looks something like this.

…Yeah, it’ll be something derp-cute, I think, but other than that, it’s on-going.

You’ll see a number of new things in the works. First, we’ve reorganized the site. 2016 and the U.S. Navy Cuisine book now have its own sections on the site, and the Pacific section is now its own thing. As I mentioned a while back, I’ve made a “timeline” of sorts detailing the tidbits and all the random stuff we’ve done for Pacific. That timeline’ll get updated as constantly as I can – there’s a lot of stuff I’m trying to finish up in the meantime.

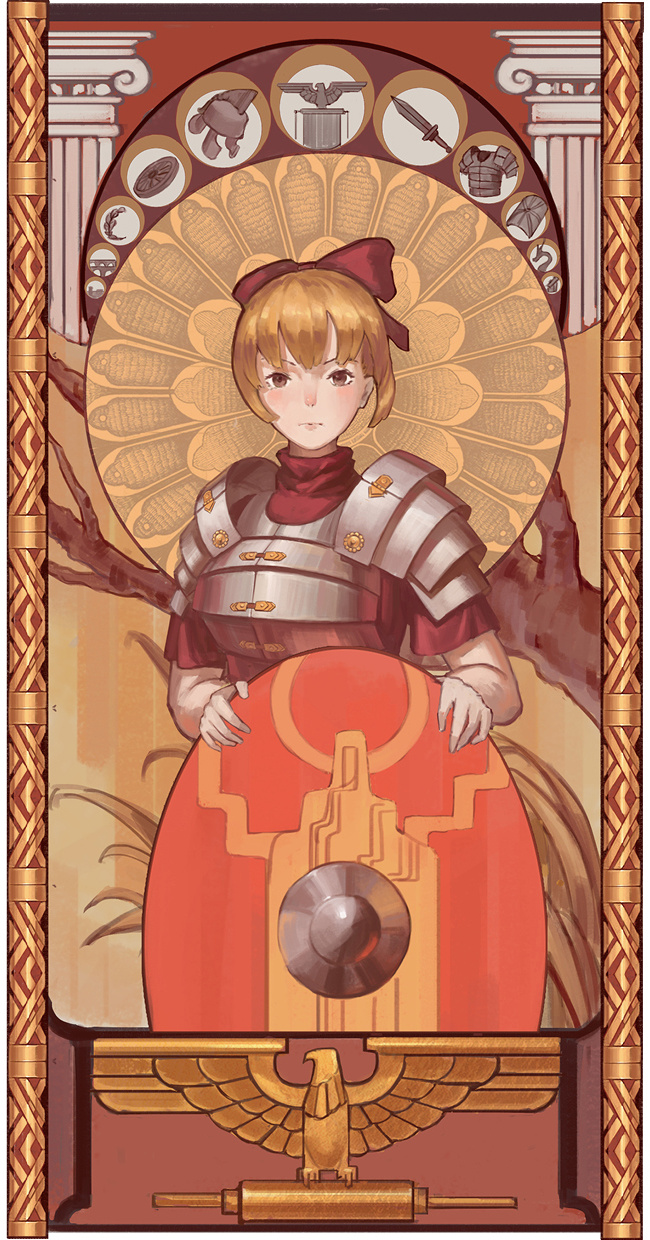

There’s another book that we’re putting out. It’s called “Fate in History.” The book is Zero’s idea about a what-if of an exhibit of Fate series characters, but as their “historical” counterparts. In particular, we’re going with the hypothesis that the historical origin of Arthur is, well, Roman.

The artist has often been mistaken for November because of his similar looking art style, but he’s not November. In a very roundabout fashion, Maria (it’s a dude, just to clarify) found us a year or so back. If you’ve seen some homebrew’d British shipgirls (sort of like Pacific, only minus the worldbuilding and the lore), he’s the guy.

Now, where do we stand with the other stuff?

We’re working on logistics pertaining to 2016. Again, if you’ll recall it took us nearly a year and a half to sort out Pacific proper, I can say 2016 won’t take that long, but we’re working on it.

Volume 3: My great uncle’s girl (his words, not mine) has been done. I think we’re good for August release, but don’t quote me on that. November is working very hard. Especially now we need to sort out the rigging so that they’re uniform.

Silent Service: All the shipgirls except for one has been fully illustrated. Sima is working on expressions and fun stuff now. By my count we have 7 1/2 US subgirls, one U-boat, one Japanese subgirl, and two Soviet ones. Below you can see an example of an expression. We’ve picked a number of expressions that we feel exemplifies the particular girl’s personality. It’s also a really easy way for us to do some stuff on the site with text and liven the page up a bit.

I think at this point Pacific has yet another inside joke.

The Royal Navy is basically cast as “Sir not appearing in Pacific” because we never get around to finishing any of the British shipgirls. For Silent Service we briefly thought about perhaps bringing the British Trout, but then we realize it’d be really confusing. That, and I’m not quite prepared to settle the lore on what happens with two shipgirls having the same name just yet.

Here in the western-speaking countries, British sources on WW2 are pretty much second only to the US in terms of the sheer quantity of stuff out there that you can get. Well, I’ve got my hands full already with the American side, and currently we’ve really got no one taking the reins on the UK. Its role in storytelling is more or less a counterweight to the US. The UK is still quite capable of influencing international politics, it’s a convenient tool for us to keep the regions that I’m not interested in (e.g. the Middle East, Africa, etc) peaceful, and it acts as a direct counterbalance to the USSR.

At the cost of Germany and to a lesser extent, France, the actual Cold War is less U.S. vs. USSR and more like U.K vs. the USSR, with the US backing the U.K. mostly except for some very unusual circumstances. Again, given a not-collapsing Soviet Union, there is always that latent threat where another war can start in Europe or worse, the spread of communism.

Pacific’s USSR is a very curious mix in that it is largely concerned with its own affairs. Not much revolution-exporting there. To policy analysts, though, there’s that latent danger. Present day, Pacific, the USSR is more or less functional. A strong leader has emerged after nearly three decades of internal bloodshed, and things have been looking up for the last ten or so years.

This didn’t come to a surprise to America’s leadership. In fact, America in Pacific is basically hitting most of our modern technological developments decades in advance of when they would have showed up in real life.

The America in this particular setting is unique. It’s familiar to us, especially those born in the 90s, but it’s still different. On average less people are crowded into large cities, driving down poverty. Manufacturing, materials, and industry are still jobs that are capable of fully sustaining a family if they wish. The average education level still lags far behind that of Europe, with much fewer people choosing to attend college or obtain higher education. However, in contrast, high school completion rates are typically five to ten points higher in comparison to where they were at here. Wages have had steady and slow increases, and Americans, too, are just beginning to reap the fruits of global trade.

These are just examples of some of the small tweaks I’ve carried out, and the resultant changes that follows. You guys have seen my writings. You know how much I love this country. It’s part of why I find Pacific fascinating.

Now, I originally set out to basically (and perhaps naively) wanting to butterfly away much of the issues in which I believed to have turned America into what it is today. It’s not that I don’t want to do so in my fictional work, but I want to make what I do meaningful.

In other words, simply “fixing it” by wiping away the past in an attempt to undo what will be isn’t good enough. What I’m focused on now is trying to understand (deeply) what will happen or what might happen if X didn’t happen. For instance, what happens if the Vietnam War concluded with a North-South Vietnam similar to Korea? Would America have been more or less prone to adventurism? How would the Civil Rights movement turn out if Dr. King wasn’t assassinated, or if he was assassinated a month, a year later? Could we have worked things out with our primary geopolitical adversary? If so, how?

I used to think that I can go in with a cleaver. If I could change X, surely the world would turn out to be better. Fast forward to today and I’m going at history with basically a scalpel. You’ll see – and I hope you’ll appreciate – how different things can be if things happened slightly differently. After all, incremental changes can result in very big differences over time.