Hi everyone! It’s Tautog again. I want to answer one question that popped up a few weeks ago. Translated, it’s something like…

“Japanese submarines had aircraft on their submarines. I was wondering if American submarines did the same?”

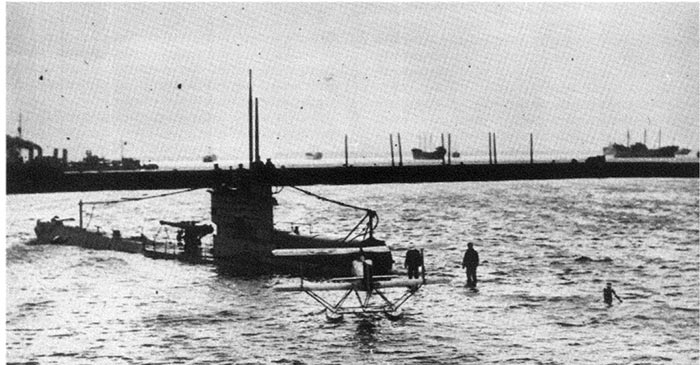

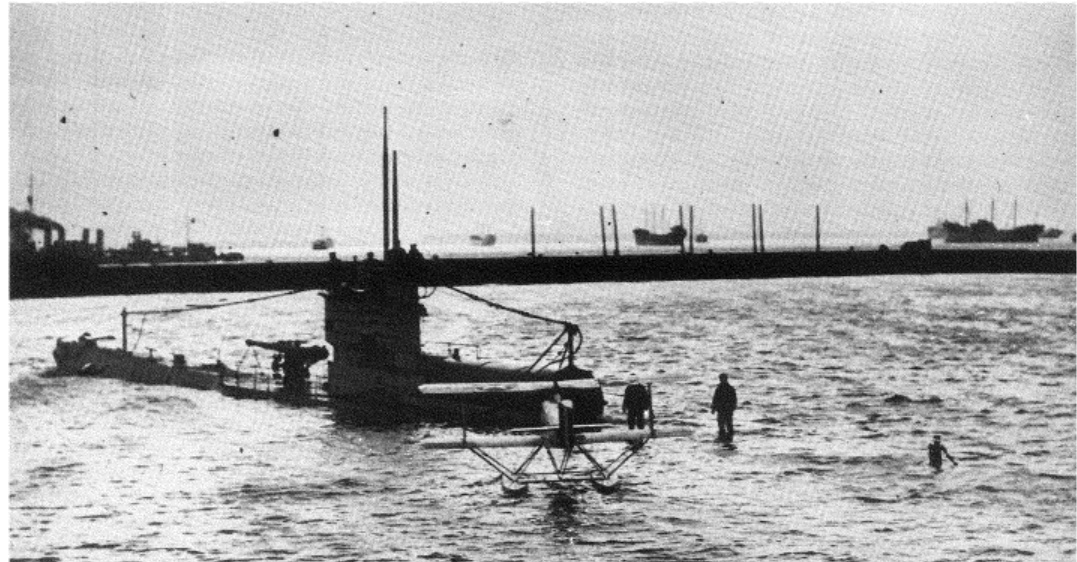

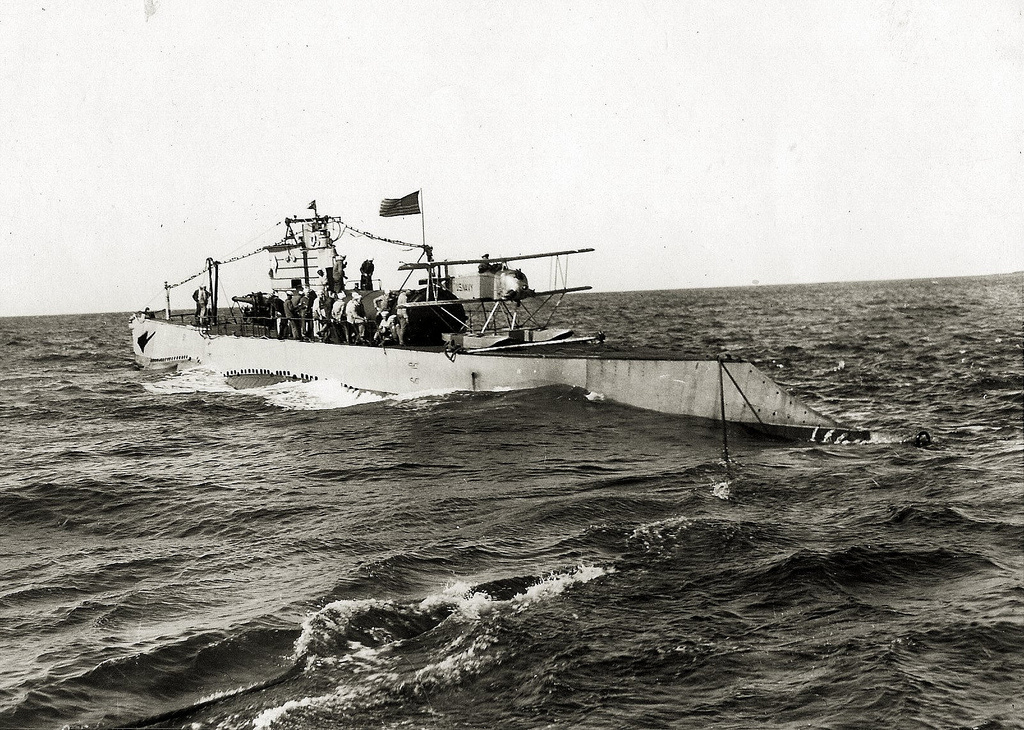

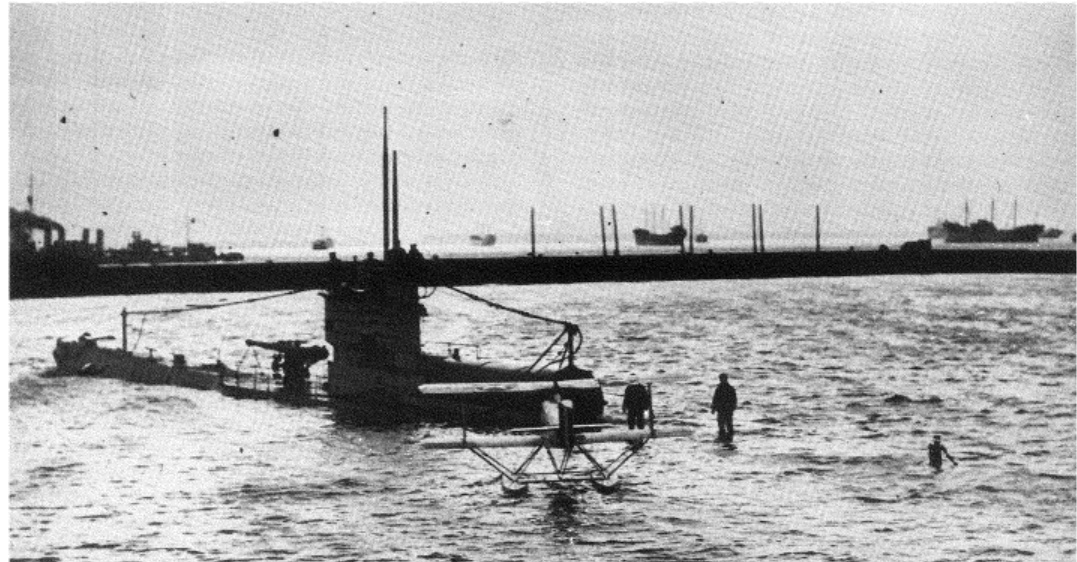

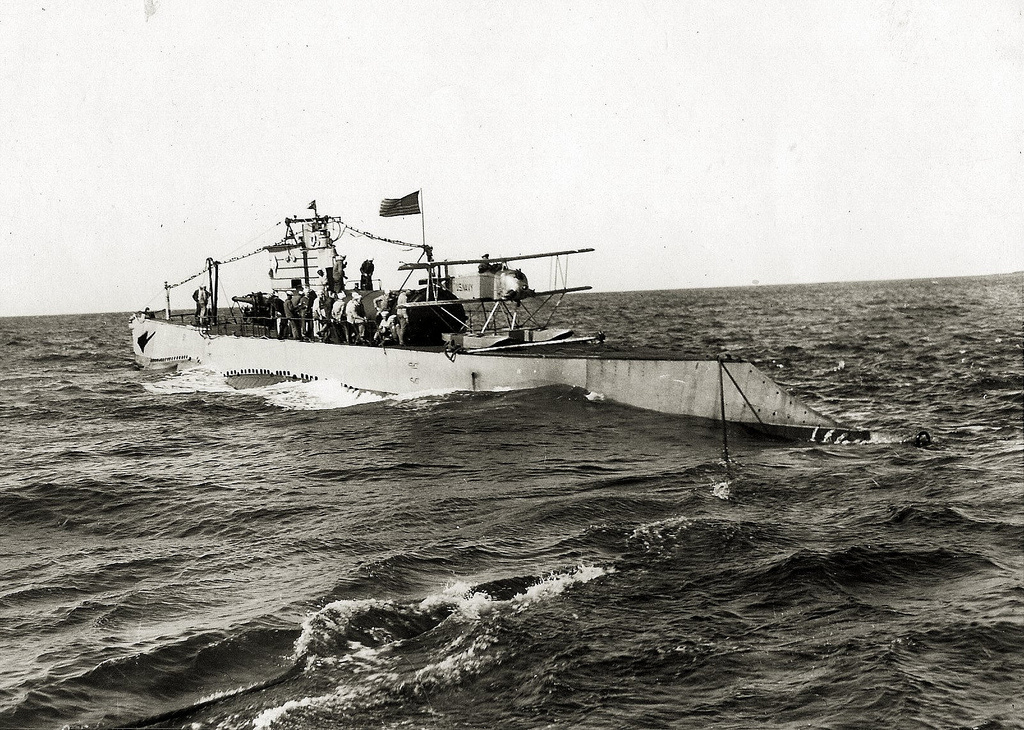

Well, the answer is yes. For a very limited time, the U.S. did briefly think about using airplane scouts on the submarine! We tried it on the S-boats earlier, as you can see below.

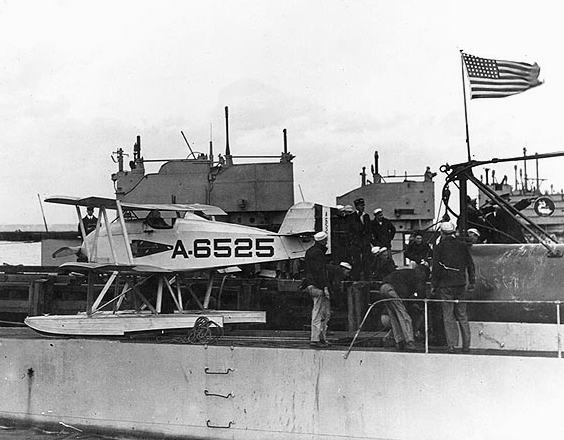

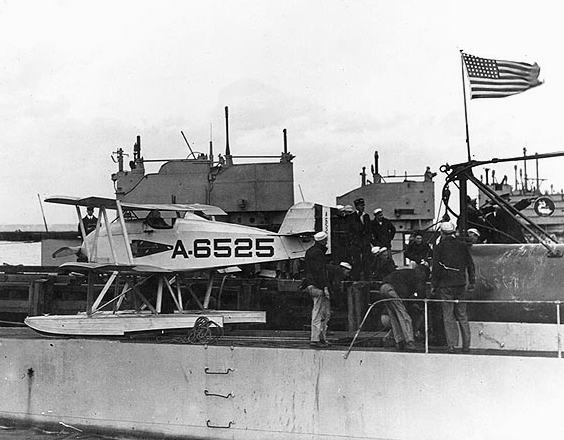

This is a photo of S 1 carrying a floatplane. Plane buffs will recognize the aircraft as a Martin-MS. A better picture from NavSource can be found below – you’ll recognize that this looks very similar to what we typically imagine as a “floatplane.” It’s just a whole lot smaller. This is the mid 1920s after all!

They also had the Cox-Klemin XS as an alternate plane that they tested.

Now, this goes back to our prior discussion on submarine cruisers. When General Board was designing that big minelayer-cruiser boat, they really wanted to see if we could fit a couple of planes onto it.

“Well, V-4 was pretty big, why don’t we try that?”

Well, there ended up being a few problems.

One, a plane is going to need a pressure-proof hangar to live in as the submarine submerges. With how many mines the Argonaut was going to carry, there just isn’t any room.

Room wasn’t the only issue though. By the way, weighing in at about a thousand pounds (the Navy asked for a two thousand pound scout plane), the planes tested were very small planes (the Zero, by comparison, was about three thousand seven hundred pounds give or take). Even these tiny things were a pain to design with, because if you think about it, adding what would basically be a big box of air really messed with your ability to stay buoyant or to go under water.

What did a submarine need? To dive or submerge as quickly as possible, of course. So to put a big hangar is already going to make your submarine bulkier and therefore more noticeable. But we’re not even talking about just having more mass. What happens if say, your hangar got damaged and you couldn’t close the door? What if the depth charges broke your pressurized hangar and causes a leak while submerged? None of those would be good for the submarine.

Of course, that wasn’t all the issues the plane faced. For starters, it took the crewmen several hours to assemble and dissemble the plane. Our floatplanes at the time couldn’t go very far either, and we had serious concerns about whether or not they can fly out the few hundred nautical miles they’d need to scout a Japanese base (remember to basically multiple any estimates you make by two since well, you want the planes to come back!), whether they would be fast or stealthy enough to get away/hide from (some) enemy aircraft, and whether they could operate well under worse weather conditions.

Secondly, the plane would need to carry a radio to signal back to the sub, “okay, bad guy here” or “everything’s clear, go,” right? How is the submarine supposed to pick up that signal safely? If you pop an antenna out that’s almost as obvious as having a periscope!

To top it all off, if the enemy detects the scout plane, it’s certainly going to lead them to the sub. If the submarine is already going to dive slower as a result of this, what would they do?

So, as you can see, while the General Board didn’t completely write off the possibility of a better submarine scout plane coming into existence later (so we could put a plane on a sub), they really didn’t try very hard after that to get a plane onto a submarine. The benefits simply didn’t outweigh the costs, and the Navy soon found other priorities that they wanted to work out.

Hope that answered your question! See you next time.