(Quick note: we have a English-Chinese translator on board now. 🙂 Thank you Ethan for the Chinese translation.)

What’s that you’ve got there, Yamato?

你拿着啥呢,大和?

Wanna try? It’s not Ramune, if that’s what you’re thinking.

想尝点?这和你想的普通的苏打水可不一样。

*sip* Lemony.

(抿一口)柠檬味的。

Mhm-hmm. Japan’s first and – if I may add – finest soft drink. Come on, dear, do you really think I’d give you something so common as any old 150 yen vendor-ware?

嗯,日本首款,大概也是最好的软饮料。亲,拜托,你真以为我会给你150日元的小店货?

Aw, that’s so nice! I bet you made this, right?

噢,真好喝!我打赌这是你自己做的,对吗?

Mhm-hmm! As much as I hate conforming to “historical” expectations (ugh, I bet if they had their way we’d all be perfect caricatures and I wouldn’t be allowed to drink anything other than lemonade), I am rather fond of these little bottles. They are infinitely reusable, and you have the freedom to bottle anything that you want. Too bad this one isn’t exactly as historical as I would have liked it. In that sense I confess, yes, I am an occasional hypocrite.

嗯!尽管我讨厌和“历史”保持绝对一致(呃,我猜如果“那种人”总能随便发号施令,我们就都得整天扮小丑演戏了,而我也不能喝不是柠檬水的任何东西了),我还是蛮喜欢这些小瓶子的。它们可以无限循环使用,你想灌什么喝都行。可惜了,我还想让这瓶子和“历史”完全一样呢。对此我得忏悔,我有时还是有点虚伪。

Hey, Yamato, I bet you know what?

嗨,大和,我敢打赌,你明白现在的情况吗?

What, dear?

怎么了,亲?

I bet you that nobody reading this article right now is looking at the soda bottle when there’s the two of us in cute swimsuits right there on the page.

别忘了咱俩都穿着漂亮泳装,我敢和你打赌,读到这儿时没人眼睛在苏打水瓶上。

Mo! No fourth wall breaking until she says so! Quick, strut a bit and uh… look sexy. Morgane wanted a historical article and we need to get this back on track!

密!别在她点头前破第四堵墙!快,摆个POSE,呃……稍微性感点。莫根想写篇历史方面的文章,我们得赶快回归正题!

Heehee~

嘿嘿~

As much as I love writing about Pacific and its alternative world, I’m almost always mindful of the fact that well, I got into all of this because I’m really fond of history. If there’s one thing KanColle managed to get right, it’s the fact that yes, game really can get people interested in things that are more than just cute girls doing cute things.

我尽管喜欢写美舰本及其平行世界,但很少忘记,嗯,我做的这一切都是因为我真的很喜欢历史。如果说KanColle搞对了一件事,那就是游戏的确可以让人们对萌妹子卖萌之外的东西感兴趣。

As the creator, though, I feel like I’m always trying to strike an unusual balance. On one hand, I don’t want to just regurgitate historical tidbits. On the other hand, a lot of the historical tidbits are very interesting and deserves to be mentioned (in part because I don’t see people do that). So while I’m trying to figure out how to write these things, one thing is certain: it’s really fun digging into details and thinking about how I can craft something so that each line contributes to the development and impression of one of our girls.

作为创作者,我总觉得自己好像在一对奇怪的矛盾间寻找平衡。一方面,我不愿只是简单的复述历史轶闻;另一方面,不少历史轶闻真的很有趣,的确值得一书(这在某种程度上是因为我没看到有人做这件事)。因此,我在尝试写这些东西的过程中,有一点从未改变:挖掘历史细节和思考如何写美舰本都很有意思,而后者的目标当然是让每个字都能进一步塑造我们家姑娘的形象并在读者心中留下更好的印象。

The particular soft drink that Yamato is speaking of is Mitsuya Cider. Sune and I thought hard about crafting this part of her character, and we thought it made more sense for our Yammy be someone who’s not only keenly aware of her “roots” as a Japanese shipgirl, but also someone who is fiercely proud of her cultural heritage. Going through the groceries that Sune brings home on a regular basis for instance, and you’ll find a lot of “parenthesis: made in Japan” or “parenthesis: sourced in Japan”. It’s from this perspective that we settled on Mitsuya Cider. It makes sense – you’ll see why in a bit, and I think it provides a really good glimpse into history.

大和提到的那种软饮料就是三矢苏打。我和紫在构思大和这个角色的这一面时很动了些脑筋。我们觉得她不仅要十分清楚作为一名日本舰娘的“根”在何处,更要对自己所继承的文化传统有强烈的自豪感,这对大和酱才更有意义。比如,仔细看紫定期购买的日用杂货你就会发现很多“日本制造”或“源自日本”的标志。也由此得到启发,我们最终选定了三矢苏打。这样安排是有道理的——你将从这一点明白大和为什么选它,并且,我真觉得这是个深入历史,了解细节的好机会。

We’ve established in Pacific that while the shipgirl’s personalities and characters are fully autonomous from their “historical counterparts,” they will retain memories, experiences, or knowledge that are directly or indirectly connected with their identity. As such, what Yamato would be aware of is the extraordinary rapid change in Japanese dietary habits prior to the Meiji restoration and leading all the way up to the war. She would certainly know, and thereby have a taste for things such as beer and soda – both of which were symbols of industrialization (and to a lesser extent Westernization) and of course, luxury at the time.

在我们构建的美舰本的世界中,尽管舰娘们的人格和性格并不局限于“历史上的它们”,但她们仍拥有当年和它们或直接或间接相关的记忆、经验和知识。比如,大和应该清楚明治维新之前日本饮食习惯的急剧变化。她肯定知道,当时工业化甚至西化的象征——啤酒和苏打水都是一时的奢侈品,因此她肯定对这种东西有她自己的品味。

The earliest advent of Japanese soft drinks, then, can largely be traced to Japan’s burgeoning beer industry. The limiting factor at the time for soft drink companies weren’t necessarily the lack of market – western drinks such as coca-cola has been positively received since the end of World War I – but rather the difficulties in producing containers that would have been appropriate. Just as the first commercial brewers for beer appeared around the 1870s, Japan’s glass manufacturing rose alongside it. By 1906, three of the largest Japanese brewery and drink companies merged into the Dai Nippon Beer Company, and it paved the way towards many of the standardization capabilities that would enable the production of an entire category of carbonated soft drinks the Japanese refer to as “Cider” (サイダー)

日本最早的软饮料基本可以追溯到日本当时蓬勃发展的啤酒工业。在那时,考虑到一战结束后可口可乐的反响不错,当时软饮料公司发展的瓶颈并不是市场不够大,而是自己无法生产足量的合适容器。随着最早一批啤酒酿造商在19世纪70年代的出现,日本的玻璃制品业也随之一道发展。到了1906年,日本最大的三家啤酒厂和饮料公司合并成为大日本麦酒株式会社。它为许多方面的标准化铺平了道路,也使被日本人称作“苏打”的全品类碳酸软饮料的生产成为可能。

Unlike ciders as we would understand it, the Japanese cider is closer to a mixture between sprite and 7-up. These ciders, including Mitsuya, were colorless and transparent. Almost all of them had a lemon-lime taste to it. Now, I’m not a real historian, but we dug a little bit into what Ramune is supposed to be, and the term is a literal transliteration of the English word “lemonade.” A cursory glance into historical and period-appropriate documents show that unlike Mitsuya Cider, which had a defined brand and a defined recipe, “Ramune” was a catch-all term used to describe these type of drinks. Anything that had sugars and had a sour/lemony taste to it can be rightfully called “Ramune.” Thus, it is no wonder that many IJN vessels had the ability to produce such soft drinks. This was a period of time where such sweet treats were luxuries, and so long as you had an adequate batch of starting materials (sugar or lower grade syrups, lemon juice or various acids), you would certainly have been able to enjoy Ramune on board a ship.

与我们今天熟知的”苏打水”(苹果汁)(莫根注:从纯粹的西方角度来讲,西方的“Cider”是指用苹果榨或者发酵过的饮料,中文似乎有苹果醋或者苹果汁这样的翻译,但怎么说都不是完全准确的)不同,日本的“苏打水”更像雪碧和七喜的混合物。包括三矢在内,这些“苏打水“是无色透明的,它们基本都有种柠檬味。虽然我不是专业的历史学家,但现在我要稍微挖掘一下lemonade(柠檬水)的音译词——“Ramune(ラムネ)”的真正含义。迅速浏览当时的历史文献后我们发现,和有明确商标和配方的三矢苏打不同,“Ramune”是所有此类饮料的泛称。任何含糖并带酸味或柠檬味的饮料都可以被叫做“Ramune”,也无怪乎很多日本帝国海军(IJN)的舰船都能生产这种软饮料。在这样的甜东西还是奢侈品的年代,只要有足够的原料(蔗糖或品质较次的糖浆,加上柠檬汁或多种酸味剂),在船上的你就肯定能享用“Ramune”。

This is what a “Ramune” type drink would have looked like during WW2. This is a bottle taken from Mutsu, and as you can see, it does not have any brands or markings associated with it. The bottles are plain, and it is likely that the taste and flavor would have differed slightly from batch to batch. Nonetheless, any ship that had the ability to carbonate the drink mixture would have been able to make this. (Whether or not there would have been enough for everyone, on the other hand, would be a very tough question to answer. Evidence – what scattered bits we can find – seems to suggest that soft drinks were stolen almost as often as alcohol on IJN ships)

这就是二战时一瓶“Ramune”类饮料的大致样子,而这个瓶子来自陆奥号。可以看到,它表面没有任何商标和标志,就是个空瓶。瓶中灌的每批东西的口感和味道很可能只有微小的差别,然而这不妨碍能往饮料中加二氧化碳的船都可生产“Ramune”。(另一方面,我们很难确定是否船上的所有人都能喝到这种饮料。目前能找到的零散证据似乎表明,IJN船上软饮料的被偷频率与酒的差不多。)

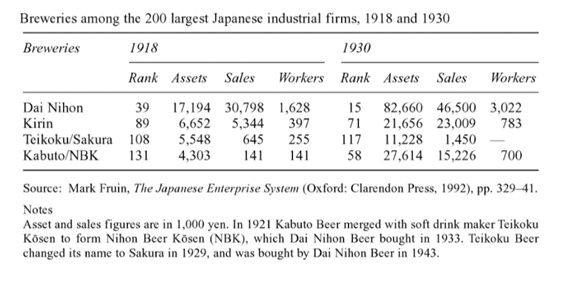

Mitusya Cider, on the other hand, was created as a bona-fide soft drink by a company named Teikoku Kosen. It was Japan’s most popular branded soft drink at the time, and prior to their merger with Dai Nippon in 1933 (and thereby becoming the largest soft-drink producer in wartime Japan), you can already see that it commanded significant segments of the market.

而在本土,为生产真正的软饮料,帝国矿泉株式会社创立了三矢苏打,成为当时日本最受欢迎的软饮料品牌。与大日本麦酒株式会社在1933年合并成为战时日本最大的软饮料生产厂商前,你就已经能看到它占据了很大一块市场份额了。

Think about this for a second. A soft-drink company can squeeze itself into Japan’s top 200 industrial firms (rank 108 to 117), in an era where giant corporate-conglomerates (the Zaibatsu) was in full command of the Japanese economy. Is it any wonder that Yamato might be interested in that particular drink, either because she’s remembering it fondly, or perhaps she simply enjoys the taste?

稍微设想一下吧,在日本经济完全受大集团(财阀)控制的时代,一家软饮料公司都能跻身日本工业企业200强(排第108和117名),那么无论大和是因为曾经就很喜欢,还是现在才开始喜欢,她对某饮料有些兴趣真的很奇怪吗?

(The picture on the left is a picture of what the Mitsuya Cider production facility looked like – and the machinery it used to make these sodas. The picture on the right is what Mitsuya Cider would have came in – in either green or olive bottles, with the Mitsuya logo emblazoned on the bottle itself. Clearly, as you can see, it does not look anything close to the marble bottles that Ramune as we know it today would come in.)

(左侧的照片是三矢苏打生产设备的大致样子,从中可以看见生产苏打的机器。右侧的照片是三矢苏打的容器——或绿色或黄褐色的瓶子,瓶上有商标“三矢”。如你所见,很显然,它和我们现在熟知的Ramune的无色透明瓶子差别很大。)

Now, you only know that Yamato “made” it herself. Did she bottle the Mitsuya Cider herself in a Ramune (marble soda) bottle? After all, it isn’t entirely inconceivable that a shipgirl like her might be living in a place where soda dispensers are available. Did she make the Mitsuya Cider from scratch, trekking to Hirano (平野) – the origin of Mitsuya Cider, where a river of her namesake also happens to run through the prefecture – to gather the materials herself?

现在,你只知道大和自己“制作”了苏打水,但她是不是亲自往Ramune(弹珠苏打)瓶里灌了三矢苏打?毕竟,她那种舰娘的住处附近不巧有苏打水贩售机也不是很难想象。她是不是从头开始做的三矢苏打?她有没有长途跋涉到平野去亲自采集原料?那儿是三矢苏打的发源地,流经那儿的一条河是它的名字来源。

That, I think, you’re going to have to ask her. 🙂 Now let’s take a look at the other thing of interest. What’s in Mo’s hand is probably one of the most recognizable things of Americana in the world today: the Coca-Cola.

我想,那你就要自己去问她了。🙂现在让我们看看另一件趣事。密苏里拿着的可能是在当今世界美国最广为人知的象征之一:可口可乐。

There’s a lot of stuff that’s known about Coca-Cola already. In fact, in some parts of America (not where I’m from, of course), a “coke” is synonymous with any kind of carbonated soft drink. There are few things that influenced American culture the way Coca-Cola did, but here, I’m going to talk specifically about how it differed from what Yamato’s having.

可口可乐的不少事都不是什么秘密。事实上,在美国的某些地区(当然了,不是我家),“可乐”可以代指任何种类的碳酸软饮料。没什么东西曾像可口可乐那样影响了美国文化,但这里我只想谈谈它和大和手上的东西有什么不同。

For starters, while soft drinks were comparatively luxurious (an IJN sailor with frequent access to it would be unlikely to see it nearly as often if he was a civilian) in Japan, the Coca-Cola was widely affordable and drank in gigantic quantities by just about everyone. The Coca-Cola was 5 cents per 6.5oz serving. At a time where other fountain drinks hovered around seven or eight cents, this was not only affordable, but it was something that made Coca-Cola unique. For nearly seventy years or so, anyone could get a coke for just a nickel. This was a policy that endured throughout two world wars and the great depression, and the vintage advertisement shown below is just one of the many examples that contributed to Coca-Cola’s success.

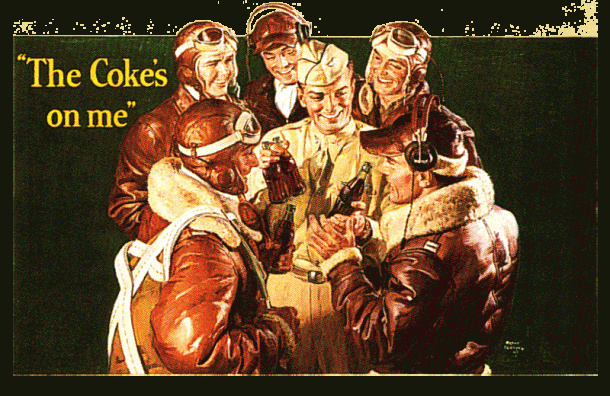

首先,与在日本相对奢侈的软饮料(一名经常能喝到它的IJN水兵如果是平民,他将不太可能仍这么频繁的喝)不同,可口可乐对各类人群都不贵,几乎所有人都喝它,每天的总消耗量是天文数字。可口可乐的售价是5美分每6.5盎司(小玻璃瓶装,约为184毫升)。与同时代售价在7到8美分左右的喷泉机中出来的其他饮料相比,可口可乐售价不仅够便宜,更让可口可乐鹤立鸡群。在将近70年的时间里,任何人都可以用一枚伍美分镍币买一份可乐。这一方针贯穿了两次世界大战和大萧条。下图的复古广告只是帮助可口可乐取得成功的诸多范例之一。

Of course, when America went to war, Coca-Cola followed. To say that it was popular was again, an understatement. Always masters of advertising, Coca-Cola was more than just a delicious drink. It was also a morale booster, and a reminder to the millions of men on the frontlines of what home was. For the record, they definitely weren’t shying away from using cute girls to get their message across!

当然,美国开始打仗,可口可乐也跟进了。可口可乐“受欢迎”这种说法太过保守了。作为长久以来广告界的大师,可口可乐可不止是好喝的饮料,更是士气助推器,提醒着前线的数百万将士家是什么。在史料中,他们绝没有羞于利用可人女孩传达信息!

Yes, no matter where America went, Coca-Cola followed. Cynics may very well point out that Coca-Cola saw a huge business opportunity, and they are certainly not wrong in that regard – it was one of the few American companies that not only did business in Nazi Germany, but actually thrived in it as well. We can discuss the ethics in another post, but what I’d like to highlight is the impressive way in which Coca-Cola was associated with America. Soldiers frequently remarked on how Coca-Cola reminded them of home. Look at the Coca-Cola ads from the time, think about how it has been a part of American life and culture for decades even prior to the war, and you’ll quickly understand why Coca-Cola was an important morale booster for troops fighting on the front lines.

是的,无论美国开进到哪儿,可口可乐都如影随形。批评家们可能会强调这是因为可口可乐看到了商机。这肯定没错:在纳粹德国,可口可乐是极少数几家不仅能营业,还能发展壮大的美国公司之一。我们可以另开一帖讨论其中的道德问题,但在这儿我想强调,可口可乐公司把可乐和美利坚联系在一起是招妙棋。大兵们时常提起可口可乐让自己多么想念家乡。别忘了它早在战前就是美国式生活和文化的一部分,再看看那时的可口可乐广告,你就能很快理解为什么可口可乐是前线军队重要的士气助推器了。

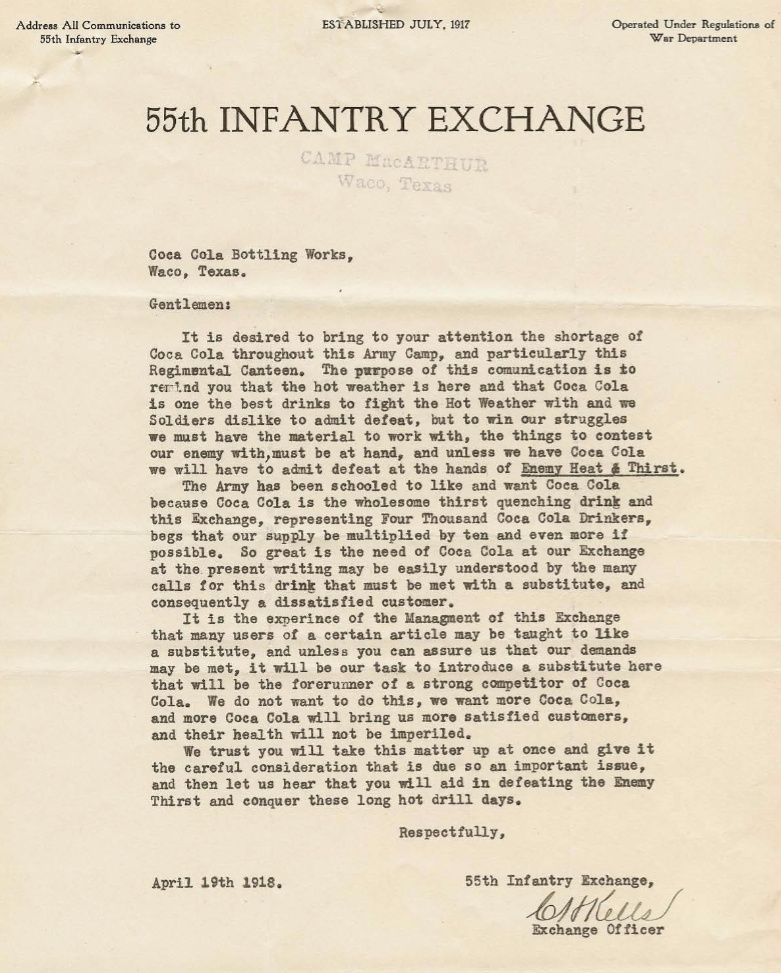

This is an example of a letter in 1918, requesting for more Coca Cola from the US Army.

这是1918年很有代表性的军队来信,信中请求美国陆军供应更多的可口可乐。(其中下划线部分就是著名的“热与渴之敌”,这正是写信者对他上述请求的解释 🙂

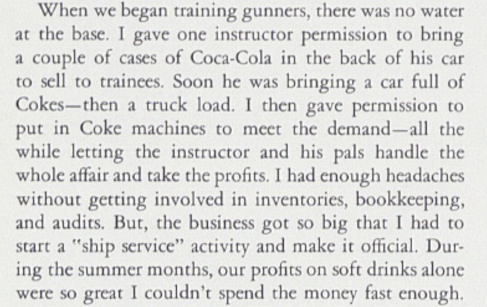

Here’s an example from the Navy – thank our translator for translating that. 🙂

在我们开始训练炮兵时,基地里没水喝。我允许一个教官在他车的后备箱里捎带几箱可口可乐卖给受训者们。很快他就开始带一整卡车的可乐了。然后我允许他装一台可乐机以满足大家的需求,我还让那个教官和他愉快的小伙伴们负责这件事并允许他们盈利。不用费心管仓储、账本和审计真是省心啊。但是!这生意越做越大,以至于我们不得不开始正式公开的做这件事并开展“航运业务”。这个夏天,从软饮料赚的钱就已经多到我花不完了。

From naval officers of FTC Dam Neck (the source from which the previous passage came from) to fountains on US navy ships, Coca-Cola was ubiquitously popular in World War 2 as well. Though, again, unlike the IJN, the US had plenty of supplies to spare. Recollection from my great uncle who served on an aircraft carrier during WW2 mentions that he remember having both bottled Coca-Cola and “fountain” cokes, the latter of which he could have as much as the mess paid for and the former were readily available in the ship’s canteen.

从汉普顿锚地培训支持中心的海军军官(上一段的故事来源)到美国海军舰船上的喷泉机,二战中,可口可乐在哪儿都一样畅销。因为的确美国人能喝个够,这是美国海军与日本海军的又一不同。我那曾在二战航母上服役的姥爷回忆道,他当时既喝过瓶装可乐,也喝过喷泉机可乐。其中后者的量要看大家事先攒的钱能备多少货,而前者在船上食堂中总能拿到。

So, I guess what I’m trying to say is that I don’t think Mo needs any particular reason to like Coca-Cola. In fact, it would be a little stranger if she didn’t. 🙂

所以,我猜我想说的是,密她喜欢可乐不需要什么特别的理由。实际上,她不喜欢可乐才奇怪呢 🙂

Alright, I think that’s enough words for today. See you guys next time.

好啦,我今天应该说得够多了。大伙儿回头见。