I have a question about the depth charges used by the world’s navies on submarines.

How did people come up with the idea? Surely an admiral did not get up one day and thought, I shall drop many exploding things on an enemy submarine that I cannot see in the hopes that one hit, right?

Actually, you know, it’s a good question. The answer is that we settled on the depth charge because it was what worked.

Let’s go back in time a bit, back to 1917.

Germany was doing a lot of damage with her U-boats. The British Admirality (along with Sims) basically tested a bunch of different ways to see if they can’t intercept the U-boats lurking all over the waters of the Atlantic.

Now, the U-boats were pretty careless at the time. They had very good radio, and so they used it a lot. What basically happened too was that the British spent a lot of time and effort breaking German codes. With some help from the Russians who provided a set of code books from the light cruiser Madgeburg and a lucky catch from a destroyer cache later, the British were able to decipher much of Germany’s intelligence in all forms.

Remember the Zimmerman telegram from history class? That should give you a reminder of just how good the codebreakers were. Even so, the British had trouble with the U-boats. Even if you knew when a ship was going to sortie, how to find it and sink it was still a challenge.

Now, back onto depth charges. You see, depth charges are really more of a “proactive” measure, as Dolphin would say. They were the type of weapon that the Admirality found to have worked best. See, in order to fight a submarine (which fights from a position of stealth), you either have to figure out a way to deny the submarine her prey, or you need to go out and hunt her down actively.

The latter had the trouble of, well, submarines being difficult to find. The former was what was tried at first. It led to some very interesting developments like the Bragg Loop. (It’s basically a bunch of electric cables laid on the bottom of the ocean. If a ship moves close to it, the magnetic field would be interrupted, and a switch would go off and tell the shore station it was linked to that someone was passing by.)

Then the navies tried to drop minefields. At the time, though, mines weren’t particularly good, and the ratio of mine used to submarine sunk was very, very low. That didn’t work very well either. The submarines just avoided the area instead.

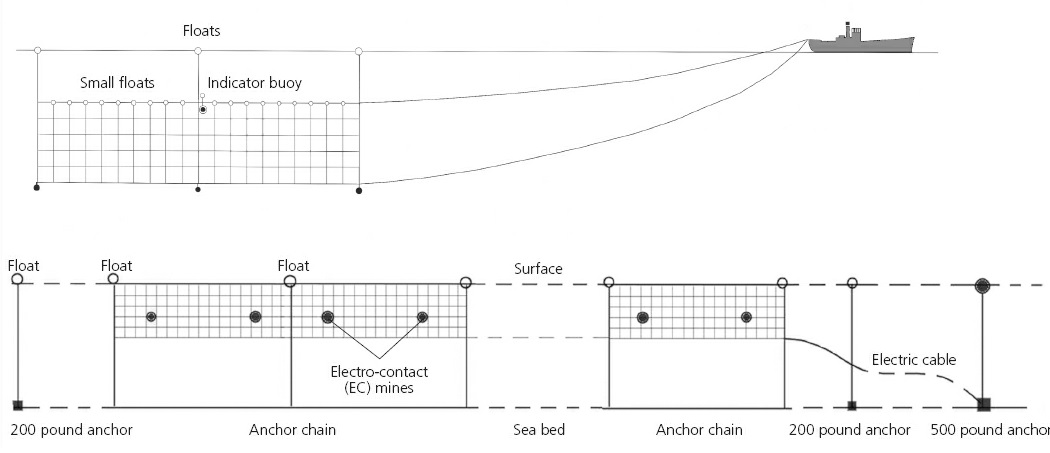

Then the navies came up with the idea of nets. Some even strapped explosives to the nets – like the picture below. I’m not sure if we caught any U-boats this way, but I do think the Germans managed to sink one British and one French submarine using stationary anti-submarine nets.

(Yeah, this was literally a very big net with mines strapped onto them. The idea was that if you set the net at a certain depth, hopefully you’d be able to catch the submarines in them.)

Others, such as Admiral Inglefield pictured above, had more creative ideas. Britain’s shores were full of seagulls. If one could train the seagulls to poop on the periscopes of the submarine, then they would be able to provide a significant nuisance to the U-boat crews.

The Admiralty briefly tried this plan out and concluded that it wasn’t particularly executable. Undaunted, Inglefield proposed that additional incentives be provided to the seagulls instead. If they were provided with a food reward like sausage or cured ham upon spotting a submarine’s periscope, then the large flocks of seagulls could serve as a reliable early warning system.

In consequence of a suggestion made by the Board of Invention and Research to test the possibilities of attracting seagulls to the periscopes of submarines by ejecting food therefrom and thereby training them to follow and locate enemy submarines, the Admirality have approved an experiment being name in B3 and have asked BIR to provide a suitable food box for the purpose.

The Admiralty relented, and provided Inglefield with some submarines who tried towing fake periscopes while ejecting meat behind. The precise apparatus was described as such.

Have a small float containing a dummy periscope; the float to contain a quantity of rough food, say dog or cat’s flesh or any other food which will float on the water. The machine to discharge small quantities every few minutes so the birds will see the food floating on the sea. The float could be towed behind a vessel at a fair distance and made so it will sink, as when the tow-line breaks.

While the researcher was optimistic that the seagulls should learn to find enemy submarines in about two weeks, it was discovered that the seagulls simply ate the bait and ignored the periscope completely.

A follow-up attempt to train hawks to do the same was equally unsuccessful. Another attempt to tactically deploy squadrons of pigeons on ships to do the same was found also to be unsuccessful.

If the theme here isn’t clear, it’s that animals are not very good submarine hunters. Before you ask whether or not they can train dogs to sniff out submarines, the Royal Navy tried with sea lions. That didn’t work out very well either (it turns out that animals like chasing after things they naturally eat instead of metal objects), but it’s probably worth another sub corner because I like sea lions and think they’re kind of cute.

Other ideas included developing specially prepared paint to be strategically dumped over areas of the sea to disorient any U-boat captains trying to surface. There were plans involving the usage of very strong lights (to blind the U-boat captain should he try a night-time attack). There were plans involving a literal formation of manned balloons to keep watch for any incoming submarines.

A lot of these plans simply didn’t pan out for well, obvious reasons. They really weren’t very practical. What was practical? Plenty.

First, the hydrophone. This is the very, very early predecessor of what would becoming listening equipment that’s found on any submarine. It’s basically a very sensitive microphone that you dropped into the water to try to hear for the noise of a submarine. Now, the earliest hydrophone at the time had its issues. You obviously could not listen very well unless your ship was stationary (you’d pick up the noise of your own ship otherwise!), and its range was very low. Nonetheless, it provided the Admirality with a good starting point, and its development really took off soon after.

Coupled with the development of the hydrophone was the depth charge “howitzer” or the depth charge thrower. You see, at the time, torpedoes weren’t particularly reliable. It was far more economical to use some sort of bomb to sink enemy submarines instead. The trouble wasn’t whether or not a depth charge can blow up a U-boat. Rather, it was spotting the U-boat to begin with.

In the days before ASDIC and sonar, the Royal Navy came up with several innovative ways to help their surface ASW units succeed. I said earlier that the hydrophone was underpowered, right? Well, the Admirality soon stringed several hydrophones together and towed it out behind an escort ship. This allows the commander of said ship to detect the submarine to a much larger range than they did previously.

Supported with aerial recon, better depth charge throwers, and more depth charges in general, one more weapon that was added to the ASW arsenal. Basically, if you look at all the strategies above, it involved for the listening of the submarine in some way.

Well, someone asked, what if we can figure out a way to detect the U-boat without listening for their sounds? What if we made some noise of our own, echo that off the submarine’s hull, and then use that to figure out where they are?

That would be ASDIC, rumored to be named after its sponsors, the Allied Submarine Detection Investigation Committee. Basically, it sent out a large fan of sound waves throughout the water. If it hits an object, the sound energy will be reflected back to the ship. Based on where your ship was facing and how long it took for the sound to come back (the longer it took the further the submarine was relative to your position), you would be able to find the submarine and sink it.

ASDIC had its weaknesses. It had a lot of false positives. It could not be used against surfaced submarines. The ship couldn’t go very fast while using it or else the positioning wouldn’t work. It also didn’t detect depth very well. Most importantly, it showed up a bit too late for World War I, as no U-boats were actually sunk using ASDIC.

Nevertheless, it was basically sonar! Had it came out even three months earlier, it would have done a lot of damage. But, that’s how war is sometimes.

Okay, I think that sort of answers the question. The next one of these I do I’ll probably talk about how naval officers during the interwar period thought about what to do – and what not to do – when it comes to ASW weapons. What you’ll soon come to realize, though, is that because it seemed like we’ve got good ways to detect submarines by the 1920s, we ended up developing that very restrictive doctrine for submarine attacks for our own submarines in the 1940s.

You know what they say. Hindsight is always 20/20. See you next time!