Tautog here, again! I’m sorry if you’re tired of seeing my mug, but Morgane’s been busy with the upcoming book releases, and so I’m down here holding the fort instead.

Today I want to talk about something that actually mattered a lot in the early days of the Silent Service. Specifically, the period around 1942 where things were really looking bad. Our story takes place in January of 1942.

The ocean was a pretty big place. How did the US submarines know what to hit, and where?

Well, you really have the Japanese to thank for that. In those early days, the IJN got super careless and started to broadcast announcements on a regular base from their big naval base at Truk. For whatever reason, they not only kept to the same route, but the information would come at noon every day.

Naturally, the submariners wanted to jump on this. Command, however, had other ideas. They were a bit hesitant in letting the submarines attack on the grounds that the Japanese might get suspicious and in turn, change up their codes.

Codebreaking is pretty hard business. So I think I should explain the basics real quick. Coding is substituting a letter, word, number, or concept with something else. This everyone get intuitively. For instance, let’s make a new cipher with s = submarine, u = u-boat, and b = buoyancy.

If I say to you SUBMARINE U-BOAT BUOYANCY you’ll immediately get that I’m really telling you “sub.” I can shift the letters around a bit, and say, s = tautog, u = victory, b = carrier. But even this message here – TAUTOG VICTORY CARRIER – would be easily broken because that’s what cryptologists are trained to do. They can recognize these patterns and try to match it to known linguistic patterns through mathematical analysis.

So, to beat this, we do something called encryption. There are many methods for encryption, but the easiest way to do it is to do something to some numbers. In the previous example, let’s say that we made it so that s = 1, u = 2, and b = 3. We can do something to each number, let’s say, multiple everything by itself.

That way, I can send a code that says 1-4-9, and only if you knew my “decrypt” – that is, the proper mathematical answer to the question would you be able to realize that the message I’m really sending is 1-2-3. Even then, you still need to figure out what “1,” “2,” and “3” are. See how this is a lot more secure?

Now, the Japanese naval code was exceptionally difficult to break. JN-25 is what we call a “superenciphered” code. In order to send or receive anything, you needed three books.

The first book had about thirty-three thousand words and letters that had a random five-digit number next to it. The only thing we know is that all these numbers are divisible by three (just in case there’s an error!)

The second book is a “decode” book. It’s pretty simple. It’s like a phone book where you can look up what the corresponding code is.

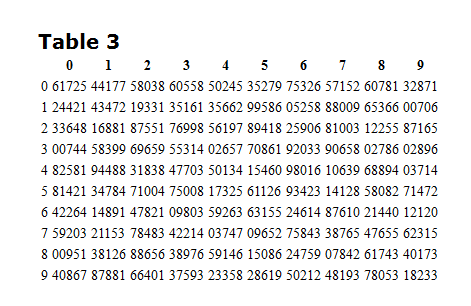

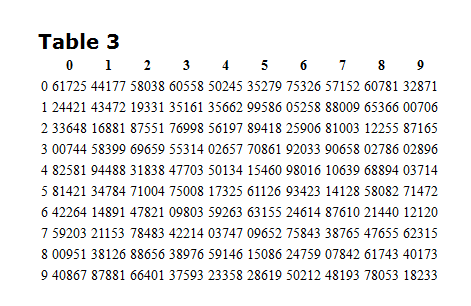

Now, you might be thinking. That’s a lot of words, but surely the more common words like Tokyo or Battleship or Fleet would pop up regularly. You’d be right. In order to make it more secure, there’s an encryption book. This book had a page number on each page. On each page there would be several tables. On each one of those tables, they had their own identifier, and within the table there are cells with random five-digit numbers in them.

So, here’s how this is actually going to work.

(Photo take from “A Tale of Two Subs”)

Let’s say I want to send a message. “Tautog is happy.” In the normal code situation, it might look something like 00003-00006-00009. To superencrypt this, I go to that table up there, and pick something random.

Let’s just say that this is page 10. I pick column 0, row 1. It’s 24421. Using a Fibonacci subtraction (where the numbers don’t affect the next column), I subtract this number to my first code, 00003. I get 86682. Moving onto the next word, 00006 (is), I move across the table and subtract 43472, getting 67634. So on and so forth.

Then I can make some sort of a code to tell my guy, you need to go to page 10, find the 3rd table, look at column 0, and start on row 1. So it’d be 10301 or something like that.

So now literally I will send you a garbled list of numbers. 88682-67634-91778-10301. Because you also have an encryption book, you can look it up, do the proper math, and then figure out what I’m communicating. Get it now?

(Side note! We’ve got an even better of this thing called ECM-2. It was never broken, too! But we’ll talk about that some other time. Gah, I’m turning into Morgane with this level of off-topic rambling…)

Now, imagine that you didn’t have either of the books on hand. You had neither the decrypt information nor the actual code.

all you had were numbers.

What’s worse, it’s not like the Japanese language is easy, either. Japanese have four alphabets that they could use. They have kanji, in which a single “sound” can mean a full word. Katakana and hiragana are closer to how we would understand an alphabet, and romaji – the Roman alphabet – is used to actually encrypt and decrypt these messages to begin with.

Think about the brain power it takes to find meaning out of thirty plus thousand individual “words” that are used to transcribe a subtle and complicated language.

Remember that Japanese are missing some sounds, too, so it makes reading doubly difficult. “Langley” is very likely actually transcribed as “Rangrey” if a Japanese speaker was pronouncing it.

Then realize that we not only managed to read bits of it, but we managed to figure out just what it is that the Japanese are trying to do.

Realize that if the codebreakers got it wrong, massive loss of life and material could result. After the success that was Pearl Harbor, the IJN was trying to knock us out of the war. Suppose we get it wrong and we lose the last of our bases in the Pacific.

It’s gonna be a much, much longer war then, isn’t it?

Well, guess what? The codebreakers were very good. I’m going to talk about some of the earlier Silent Service battles in a later post – probably right around the time I finish up the early designs section. But just know that the submariners took the information very seriously, and just as they managed to deliver, so did the Silent Service.

See ya next time!