Hi everyone! Tautog here. I’m back with the next installment of the sub corners.

Honestly sometimes I don’t know if anyone other than me reads them… People seem to be way more interested in bikini-clad shipgirls…

Oh. You read them?

Well. Then. Yay.

Anyways. By now we’ve gotten into the “modern” submarines. Okay, well, not so modern, but the type of submarines developed are beginning to approach how we’d actually use submarines.

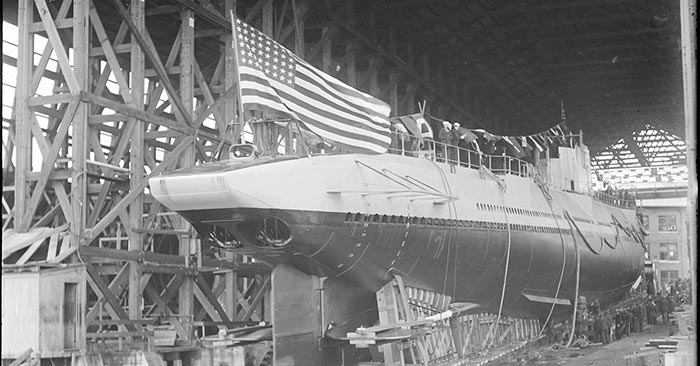

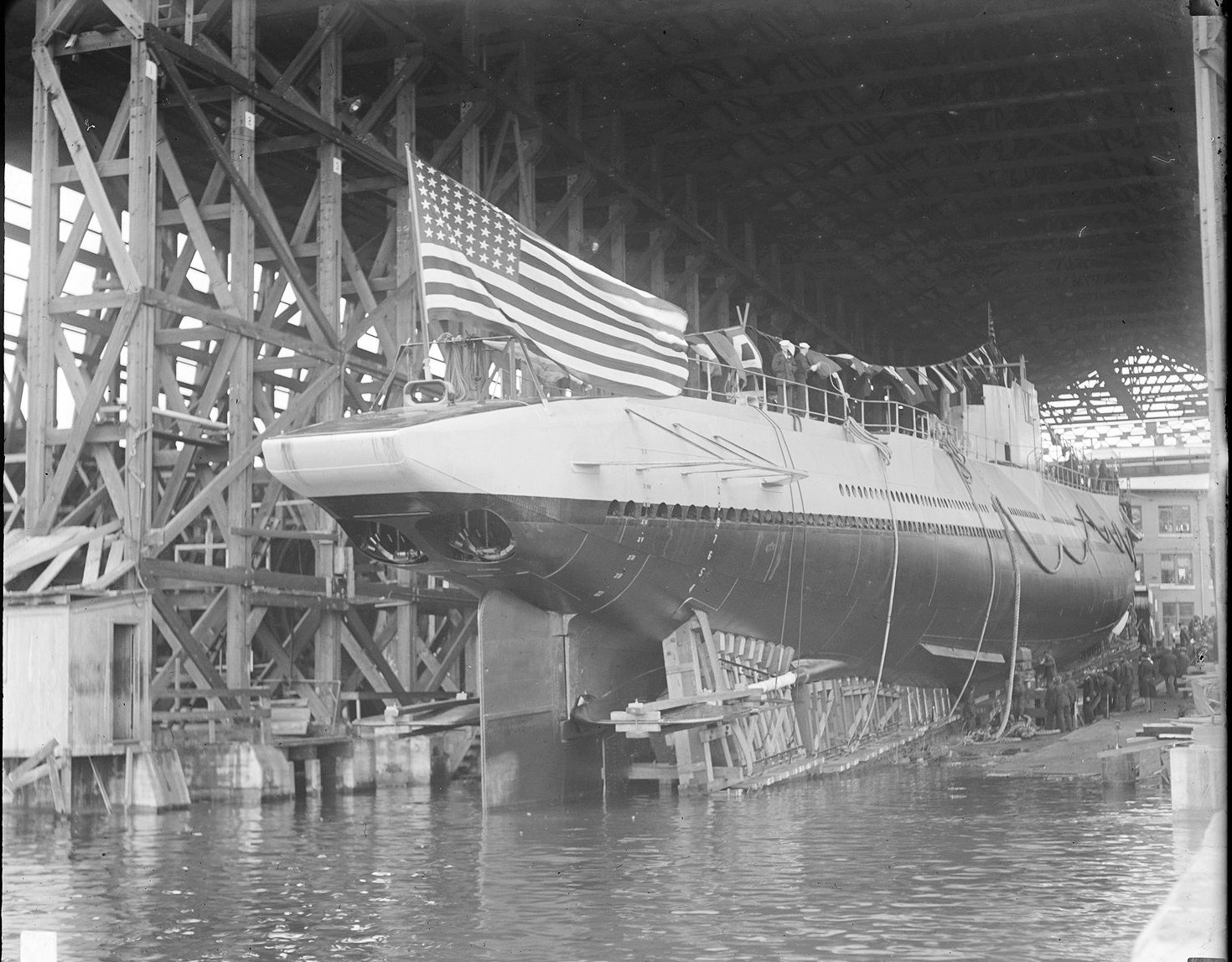

At this time, we were still largely running around like headless chickens in terms of designs. But, scared into action by hearing Japan building a lot – up to forty-six large submarines – they went to Congress and asked for more subs. As you know, Congress only authorized the one big sub – that’s Argonaut, which we started to talk about last time.

Now. The Argonaut was big. It was 4,160 tons submerged and 116 meters long. Imagine the length of a football field. That’s pretty close to how long it was. It’s got most of the things that the Navy wanted. Good range – 18,000 nm. Good – okay, okay speed at 10 knots. A big armament load with four bow tubes and sixteen torpedoes in total and two mine tubes (shown in that picture up above). It’s also got two nice big 6’/53 guns to shoot stuff on the surface if it would want.

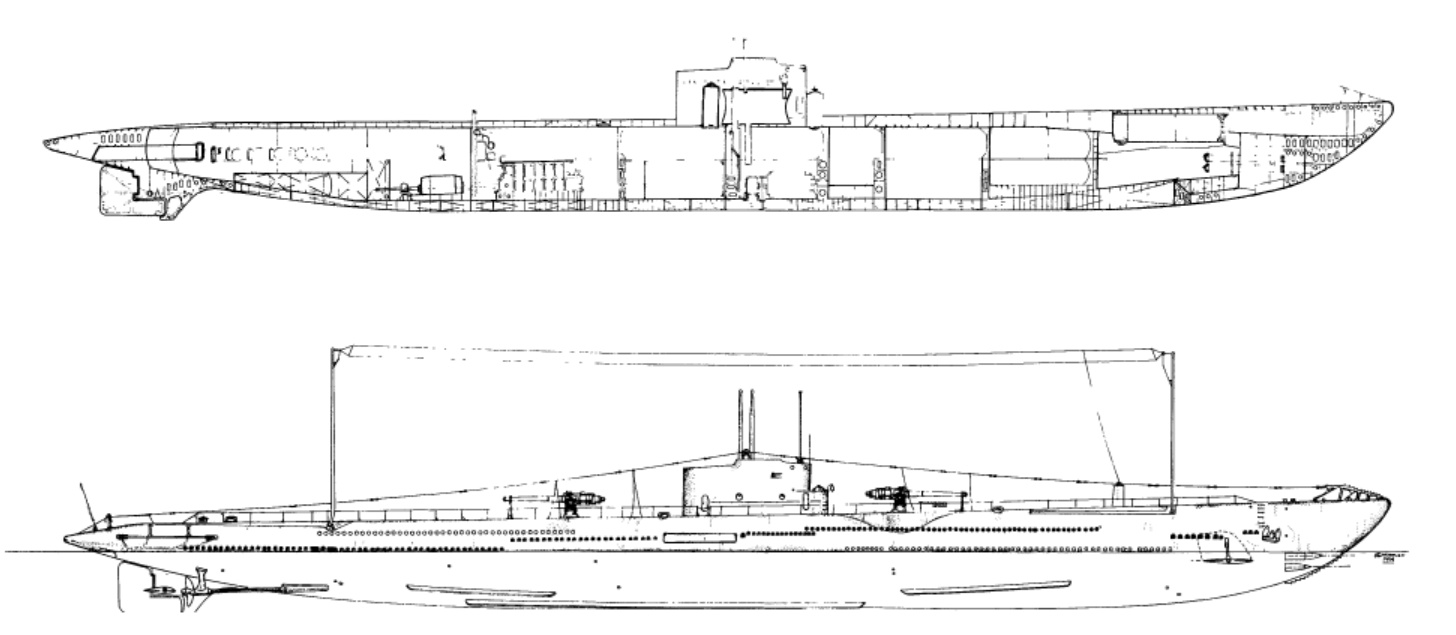

Now, mines. This particular type of sea mine was very similar to the German designs. If you look up the UE II type submarine, it’s the same idea. The mines were stowed inside the pressure hull in place of a set of after torpedo tubes. They were placed on racks that were kept water tight – and the racks themselves were complicated pieces of machinery involving worm gears and a lot of moving parts. Though, I’m not sure if I’d like the idea of sleeping right next to mines since the crew compartment was quite literally one section after that!

Yeah… That’s a blueprint of the Argonaut. I’m sorry I’m not quite explaining the rack-mine thing very clearly, so you’re gonna have to squint at the picture to get a better idea of what I’m talking about.

Anyways, the mines that were supposed to be carried by the Argonaut were unique. The Mk. 11 mines had more explosive power than the conventional Mk. 10s, carrying nearly 500 lb of TNT as its explosive charge.

Funny, since the Argonaut never actually laid any of these mines during wartime.

Wah, you scared me! Hey Argo. Okay. Well. Why don’t you explain this then.

Okay. Sure. So, a couple of issues ended up hampering actual minelaying operations. Logistics is the first one. At the start of the Pacific War, the Navy only had something like 200 Mk. 11 mines on hand. They were, as you can imagine, all for the Argonaut.

But that’s not really the issue. First of all, nobody really liked the mines. It squeezed a lot of space out of the sub which could be used towards fuel or better living conditions. Secondly, you know how submarines normally laid mines?

Through the torpedo tube?

Yeah. So if you can do that, why bother installing special dedicated mining equipment that gave everyone else trouble? Why make an entirely separate type of mine that only this one submarine could use? Can you imagine how hard it’d be to train submariners given how unique the equipment was? Prototype, one of a kind, special snowflake things belong in the realm of cartoons or video games. They’re absolutely horrid for an actual war.

Then there was the matter of age. Designed in the 20s, the Argonaut was an old ship by the time we got to the Pacific War. The Navy still harbored ideas that she might perform her original task, but by then, submarine doctrine has evolved considerably and she was needed on other tasks. The Mk 11 were powerful mines, to be sure, but if you look at the Argonaut’s war patrols, she never had “time” to perform a mining operation. What ended up happening was that her huge size found use in other tasks that only submarines of her size could do, and that was the Makin Raid in 1942.

…Look at it this way. The records say the mining gear wasn’t stripped out of the Argonaut until right before the raid. Not even her refits resulted in the removal of that equipment. I think it’s fairly good to say that the Navy at least still had ideas to have her lay mines.

Yup. The Navy thought that if we mixed up Mk. 11s with the regular Mk. 10s it would be harder to sweep. What ended up happening was that no Mk. 11 mines were actually laid (to my knowledge) during the war. To that I say, what a waste of perfectly good explosives…

Heh. Anyways. Should I?

Oh yeah. I’m done. I just popped in to check on ya is all.

Okay. So. Back to the earlier comment. Again, going back to the mines, the mines made it so that she had very poor surface speed. Remember she should have made 14-15 knots, and could only do 2/3rds of that. This was eventually partially addressed in a refit, but this was one of our slowest submarines that serviced during WW2.

Though, even for her time, there were other strengths that compensated for this particular design weakness. For starters, this was the first time American submarines used that horizontal cylindrical conning tower design, which would eventually become standard. There were plenty of attempts to improve habitability – bigger crew messes with better refrigerator storage, even room for air conditioning later on. It had a periscope with a retractable fairing on it, which reduces vibrations from the wave it forms. It had twice the battery volume of the earlier submarines (240 cells rather than 120), and all in all, she was adequately serviceable.

Oh. It also had a very big gun. The six incher’s shell had twice the destructive potential compared to the 5 inch and also shot straighter. So, definitely something to consider!

But, at the end of the day, these large submarines were not very well received. The submariners hated them because they were awkward and very uncomfortable to work in. The engineering was tough to get right and a lot of equipment complexities and design flaws surfaced which had to be corrected. Congress didn’t like them either because they were very expensive.

To top things off, we weren’t sure if they’d actually do what we’d like them to do during war either. The underpowered engine was a real killer, and again, the low speed…

…

I know you like to think that all of our submarine designs were complete winners, Tautau. But, you know, some were more winner than others. This one, well. I’m just gonna say. It was a lot less of a winner than the other ones.

Aw…

She was a good boat. Did what she was supposed to do. Couldn’t ask for more than that. Right?

Right!

Well. See you next time, everyone!