STEC Archives, Audio Documentation Division

Curator signature: [Classified]

Format: Audio recording, magnetic sound recording

Object: Recording, Fragment, Statement of Cmdr. Conrad Wallace

Location (if known): Unknown. (White House?)

Time (if known): September 21, 1950.

I thought Savo was bad. But as you can see, the losses we suffered are catastrophic. Even now, to speak plainly, our ability to interdict and intercept the enemy has been severely curtailed. Mr. President, I know from our correspondence that you’ve read all of our reports and commented extensively on them. I just want to stress the nature of the disaster and how serious the appearance of that thing is for our own national security.

(Identified as Harry S. Truman) I know. Again, like I’ve told the boys from the press, if you ever pray, pray for me now. I’m absorbing what I can, and there’s an awful lot of it that I don’t understand.

Mr. President, I understand –

Drop the Mr. President. This discussion is between Harry Truman and Conrad Wallace, two concerned Americans about our country’s future.

Yes sir.

So what have you boys & Iowa found out?

A few things. First, I would like you to look at this report here.

The one from the army, yes. I must have gone through that five or six times already. The only thing that I got from that, was that the only unusual thing was a complete blackout on land with no visibility. None whatsoever. Is this true?

Yes, sir. That’s the first thing I’d like to bring up. Here are aerial recon photos taken based on the last call from the 8th recon. As you can see, visibility was normal. Resolution was fairly good. No sign of any sort of black-out or darkness as we can see. However, given the consistency of the reports from air, ground, and sea, it’s pretty reasonable to conclude that the men are seeing something in the field. Whether it’s an “impenetrable fog” or “black mist” or “sudden darkness”, what matters is that it cuts off visual perception of the target and severely disrupts all form of communications.

Hold up a second. That doesn’t make sense. Let’s say that this thing’s making the darkness. Okay. So why isn’t it attacking under cover of darkness as well? Why is it giving our boys a chance to shoot back?

Iowa thinks that it’s purely intimidation.

…

I’ll be honest, sir. The only reason why we won that one was that we got lucky and the monster got cocky. According to Iowa, who claims to have fought these monsters before, their typical mode of attack IS more or less brute-force. After seeing what it did to our ships and our men, I don’t doubt her for a second.

Damn bastard. Against what we’ve got in our arsenal, it’s functionally invincible.

Yes sir, and I am of the opinion that the men of the 8th knew that. You’ve read the latest briefing on the matter?

Only what’s been on my desk so far.

We were able to retrieve a number of items from the 8th recon.

*Silence, then an audible intake of air*

Yes, sir. They realized that it was a trap almost immediately after they’ve sighted the enemy. It wasn’t just the 8th and the marines that were trapped in there. The Koreans had entire divisions in the area, but by the time the 8th reached some of their fortifications, it was too late.

Too late … for our boys, too.

Yes, sir. If we can take solace in the matter, it’s that we have certainty on at least one thing the enemy can do. It has the ability to disrupt communications. The 8th was able to only send out one message requesting an evacuation, after of which all of their radio transmissions became garbled nonsense.

It was bait.

Yes sir.

And we took it because of course. Of course! We had no idea that it was there. For all intent and purposes we thought it was Kim’s men hitting us.

Yes sir. The 7th fleet did what we would have done under normal circumstances, and we sent a relief force immediately. Our men were well-trained and well-disciplined, and it was our own discipline, ironically, that sealed the fate of that entire task group.

In hindsight, had we even hesitated for perhaps half an hour, we might not have lost that carrier. I might not have sent eight thousand men to their deaths. But … what happened happened.

It is impossible to talk about STEC’s early history without Conrad Wallace.

Consummate, meticulous, and coldly analytical (possibly influenced by his engineering degree), Wallace was a perfect fit for the Navy. He was never one to raise his voice, but his imposing height (6’10”) placed him literally heads and shoulders above his colleagues. His command was characterized as bold, favoring decisive actions and steadfastness after a decision has been reached. While his service in WWII was remarkable in itself, today, Wallace is better known as one of the founding officers of STEC.

Being the unfortunate man who happened to have been in charge of the 7th’s relief task force, it was natural that the spotlight was placed on Wallace. Congress, in dire need of a scapegoat, pinned the blame on the veteran officer. In a frenzied reaction that perhaps saved the man’s career more so than anything else, a general court martial was ordered. Yet the case against Conrad Wallace was so thin that three investigating officers recommended dismissal, a fourth resigned inexplicably from the case, and the last completed the Article 32 investigation only reluctantly out of a sense of duty for due process.

By the time the charges against Wallace fizzled out, he was already comfortably settling into his new role. Truman had appointed him along with a select core group of officers to a fledgling organization called the Special Task and Evaluation Command, or STEC for short. According to STEC’s own legends, the president noticed Wallace’s obsession for the abyssal fleet, and approached him with an offer, promotion included, so that he would be legally authorized to lead the organization. Wallace, true to his personality, turned Truman’s offer down. He wanted neither leadership nor authority. He just wanted to get to the bottom of it and do his part, whatever it may be.

To Wallace, the abyssal threat was more than just a matter of doing his duty or protecting his homeland. This threat was personal, and his service a simple debt of honor, to be repaid on behalf of all the men that were lost under his former command. Furthermore, as commanding officer of the relief operation, he was as close as anyone could get to the center of the event. Even if Truman did not approach him with the mission, it is probable that he would have volunteered for it. Conrad Wallace was not one to sit on the sidelines. Never was.

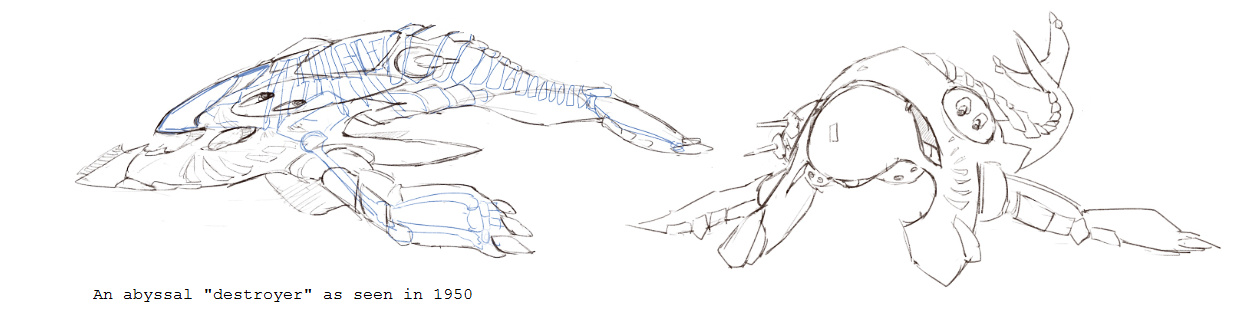

Yet the first mission Wallace received was an impossible one. STEC’s goals, on paper, was to establish a logistical and support infrastructure to counter future abyssal operations. To do this, STEC first needs to know what exactly the abyssals are capable of. That question soon became unanswerable for one reason: the abyssals were functionally unstudyable.

Whether an intentional design or not, the “corpse” of the abyssals have a tendency to dissipate into fine particulate matter. This “decomposition” occurs within minutes to seconds, making the study of abyssal components or weaponry all but impossible. Wallace had known this to be a possibility based on the information he obtained from aerial observers and Iowa’s own testimony, but he was unwilling to throw in the towel until all the tests came back empty. And empty they did. Whatever material the abyssals were made of, their disintegration was so complete that no remains could be found, and none of the wrecks recovered showed anything beyond what was ordinarily found in the environment.

So Wallace turned to his next best source: people. Out of the handful of survivors he did manage to rescue from that day, only four remained out of the original group who met with Iowa on that day. All had taken their own lives or died under unusual circumstances. Of the four that were still living, one was in a vegetative coma, and the rest were institutionalized. Despite having access to the new Veterans Administration (VA) Hospitals and the best medical care to veterans at the time, American psychiatry at the time overwhelmingly focused on psychodynamics and applying psychosomatic medicine. The psychotherapeutics of the time, applied and designed for relatively normal individuals suffering from relatively benign states, had no answer to these poor individuals touched by the abyssal fleet.

In an era where medical practitioners were still grappling with the fundamentals of mental health, Wallace correctly deduced that the survivor’s mental states were intrinsically linked to the abyssal attack. He quickly funneled what available manpower STEC had its disposal towards the confirmation of his hypothesis. Over the next few months, Wallace’s men documented and interviewed hundreds of men who were involved in some way with the abyssal incursion. The results were chilling.

Consistently, those who were found to have been involved in the mission reported sensations of dread, as if something has gone wrong, though few could explain what the feeling actually entails. Radio and comms personnel furthest from the action were not exempt, as they report a sensation of gloom or depression. Ground troops nearest the area reported a haunting sensation of abandonment, with several commenting that the despair was enough that the thoughts of ending their lives was up for consideration. Pilots flying near to where the abyssal was located overwhelmingly reported a desire to turn back, and those who were willing to admit it stated frankly that the urge to crash into the ocean was strong as they approached their destinations.In each and every case, the sensations were the same. What’s more, almost all interviewees report a wide scattering of various psychological malaise, ranging from insomnia to hallucinations to downright psychosis. The only thing constant was that in all the severely affected individuals, recurring nightmares were persistent. As symptoms worsened, the nightmares would increase in intensity, too.

It then became clear to Wallace that some key component was missing from his understanding of the events. With what evidence he had gathered, there was a simple hypothesis: the potency and the frequency of these effects is a function of the exposure and the proximity to the abyssal in question. The closer or the longer the exposure, the greater the effect is. This sensible explanation was contradicted by the data he had on hand. In fact, the biggest anomalous datapoint was Wallace himself. Despite having been in contact with the abyssal during the entire incident and even having heard the “scream,” Wallace did not experience any of these symptoms. Neither did a sizable portion of his staff or fellow officers.

Despite the fact that he had no operational hypothesis, Wallace nonetheless completed a through report on his findings and delivered it to a number of key individuals, one of whom was General Paul Hawley. Hawley concurred wholeheartedly with Wallace’s recommendations, and soon, the vast resources of the VA medical system were directed at finding an appropriate treatment.

Unfortunately, it seemed that whatever it is that affected the survivors was beyond the powers of modern medicine. Every now and then a particular methodology or prescription would seem to dampen the effect, but the nightmares always seem to return with a vengeance. In most cases, the treatments simply didn’t work. While it is not to say that these treatments were completely ineffective (in fact, many of them would become the foundation for future medications or treatments available to you, dear reader), there was nothing that seemed to offer a permanent solution to the issue of nightmare.

As reports – almost all negative – flooded back to Wallace’s office, the man grew despondent. In his desperate quest for a cure, the former Commodore moved into STEC’s newly built offices so that he could have his hands on data first thing in the morning. Finding a solution to what he saw but could not understand became a greater personal obsession, and as he worked harder, his health correspondingly declined.

Finally, it reached the point where Wallace realized that it was no longer constructive for him to work as he did. Taking the first long vacation in years, Wallace decided to take two month off from STEC and spend more time with family. It was then that the solution to his query hit him – in this case, literally via his own institutionalization.

Wallace himself remembers little of the vacation itself. Only that the first two weeks were full of family joys and much-needed rest. What he knew, however, was that he seemed to have spaced out for a brief period of time as he went outside to get the morning papers the following day. When he came to, he was securely strapped to a hospital bed. The nurse on attendance told him that he has been a gibbering wreck for the last two weeks, where he would slip in and out of consciousness fighting nightmares that only he could see. The medical team tried all sorts of protocols and medication to sedate him, but nothing worked. At least, up until now, anyways. He seemed to have cured himself.

Even as the experience slowly flooded back into his mind, Wallace’s initial reaction was closer to measured elation than jaw-dropping horror. Now, at last, the data made sense. What still didn’t make sense was what triggered the episode. To that query the nurse shrugged. It seems that the medical team, too, was asking the same question, and they were just as in the dark as he was. In any case they would like to keep him for observation for a couple of weeks at least, and the nurse offered him a pile of diversionary materials – mostly books, papers, cards, and notes from well-wishers – as he waits for an update from the medical staff.

Seeing no obvious reason to leave, Wallace took the offered bundle. Almost immediately, however, he recognized something unusual sitting on top of the stack. It was a stack of pages torn from the hospital’s guestbook, signed by many of his colleagues and dated two days ago.

Instantly, something clicked in his head.

Electrified, Wallace flipped through the pages. Sure enough, there it was. A simple “Please be well soon” written in a simple and unadorned hand.

He realized that he had forgotten one thing when he was factoring his initial hypothesis. All this time, he and his staff officers have been working in close proximity with a ship girl. Is it any wonder, then, that he and the men at STEC did not feel the effects? If the ship girl could fight off the abyssal, might she not also hold secrets to curing the affliction?

In fact, it all made sense now. How could he not have seen it before?

One hurried phone call to his wife and eight hours later, Conrad Wallace was on a plane bound for California.

This time, things will be different.