Tautog here! Heh, bet you were wondering where we’ve been up to. This post is written out-of-universe. In-character, but “out” of universe.

First things first! I fixed the website plugins. Now Morgane really doesn’t have to manually clean every article we’ve ever posted to make sure it works.

Secondly, this post is one of these sort-of in-universe works. I thought about how to do this, and I think it makes sense to do it with me talking directly to you instead. We’re going to use the development of a real-life plane to explain a bit about how STEC chooses to proceed against the Abyssal Fleet.

Also, the reason why I’m doing this is that I tend to be interested in the history and events that lead to something’s development, in addition to the hardware. Plus, it’s good for me to learn about other American things too! Planes are neat too!

…Also I, uh, totally didn’t lose a bet to Prisse or anything. Totally didn’t. Nuh-uh.

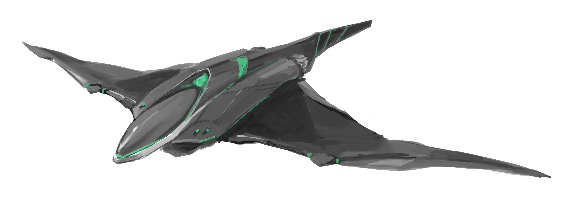

You see the plane in the cover page? Most of our regulars know what plane it is, but for the newcomers, that’s a F6F Hellcat. Since this is my website and you’re reading my opinion, I think it’s one of the best naval aircraft the war’s seen. After all, her official tally was an impressive 5,155 kills.

“Well, achshully…” I can hear the whining already. “What if *huff* it was in Youruuupeeee?” “The corsair was faster!” “It wouldn’t have worked against the wunderwaffen (insert name of prototype paper plane here)!”

Some of these points are valid. Some can be debated – though I’m pretty certain if like, Japan never existed and the war was solely over in the European theater we would have developed things a bit differently.

This brings me to the take-home message of today’s post. If we consider things on the basis of development and the principles of warfare, the Hellcat is excellent.

To put some things into perspective, in 1938, while the Navy was testing the Wildcat, we can see from correspondence that Grumman was already tasked to make a better plane. Unlike the Japanese whose aviation development was hampered by its doctrinal thinking, we were pretty sure the folks we were fighting are going to be putting better aircraft in the air.

The main goal? Make the plane go faster. Remember, the earliest records we can find of something like the Hellcat is late 1938 (!), with full-on prototype development and design taking place in 1939 & 1940. This is a time period where we were taking some pretty radical steps with fighter design. While Vought was working on the Corsair, Grumman was trying all sorts of new ideas. Look up the XF5F to see an example of what I mean.

Before that, though, a few trivia questions! Let’s test your knowledge.

Trivia question. When did the Zero enter combat?

Officially, in September of 1940.

When did we find that Zero wreck in the Aleutians?

We found it in August of 1942, and started testing it a few months later.

When did the mass-production model Hellcat get build?

September of 1942 (this is the F6F-3).

When did the Hellcat formally enter combat?

August of 1943.

Here’s a few points that I want to make.

The popular conception that the Hellcat is developed in response to the Zero is accurate (with a big asterisk next to accurate). We know from ONI that the instant the Zero showed up in China in 1940, we were interested in making something that could counter it. This information is recently declassified (i.e. within the last 10 years or so) so it’s relatively new.

The popular conception that the Hellcat was built because of the Aleutian Zero discovery (aka, the “muricans cheated nippon ichiban banzai” crowd) is wrong, unless American industry and design is so efficient that it is able to generate a mass-production model within days of the encounter. That Zero did give us a lot more information on how to fight it, but it’s the cherry on the top rather than the whole milkshake.

The understanding that the Hellcat’s design incorporated wartime experiences against the Zero is accurate, but the process is a bit more complex than you have imagined. Again, newer documents from ONI shows us that we managed to fish out about a half-dozen to nine Zero wrecks (the sources for this I’ve seen differ slightly) in the Pearl Harbor raid. The data from this was made available to Grumman sometimes in early 1942. Additionally, we know from Grumman’s own records that veteran pilots from the Battle of Midway and Coral Sea was invited to provide input on the Hellcat’s design in June 23rd, 1942 (or basically a month after Midway), where they were shown the initial Hellcat prototype (XF6F-1).

Remember that the Hellcat’s mass production model was in production two months later. That’s pretty impressive, isn’t it? Especially considering that the F6F-3 specifically had those considerations from said pilots in mind baked into its design.

See, in terms of aircraft design, the U.S. Navy had several points that I think proved to be very fruitful. These include:

- Designs had multiple models and engines in development. Capitalism and fair-competition-driving-innovation aside, this was also just practical. Imagine having engine issues and having only that one engine type. You’d risk grounding your entire air wing!

- Designs were generally flexible and adapted rapidly to feedback – that is to say, there is a formal mechanism or formal inertia for U.S. military officials to work with the design companies to incorporate combat experiences into the design of their equipment. I don’t actually know if this is the case for the other countries, but my very good Japanese friend says that based on her searching, this appears to have been a lesser priority. When we’ve got time, we’ll look into the other navies to get an answer for this one.

- Innovation. I know it’s basically a buzzword at this point, but Grumman’s design for the Hellcat ran contrary to “doctrine” at the time. Recall that during this time, the aviation craze was finally taking off (pun intended). At the time, the focus was on how we can cram as many aircraft onto a carrier at a time. Small fighters. Folded wings. Smaller bombs and ordnance. Anything that could save space. Take a look at Vought’s Corsair. Again, pretty good example of something from this era of thinking that ends up working out pretty well, but there were definitely some that didn’t.

What Grumman did with the Hellcat is unorthodox for the time. That’s not to say that they didn’t consider any of those things (because, well, having more planes in the air is a good thing), but the Hellcat’s design definitely went another way. In fact, I always get a laugh when people use the “flying brick” as an insult for the Hellcat. For one, you gotta be really bad to be shot down by something as “slow” as a brick, and the Hellcat was definitely not slow. For two, “brick” is about right for how durable it is, both in terms of its airframe and its manufacturing process. - This brings me to my last point. The Hellcat was designed in such a way that it was from the ground-up potentially capable of carrying out multiple tasks. You know how the Sherman had a ton of different variants that more or less did the job pretty well? Same with the Hellcat. The overall configuration didn’t change much, but as soon as the first Hellcat units hit the field, Navy was fiddling with other stuff. Can we add radar to it (Yes, got it working basically a year later)? Can we use this as a fighter-bomber (We could, but fuel tanks for greater range worked better!)? What sort of changes can we make to make to this thing?

Oh, by the other stuff, I mean that the Navy never forgot its primary purpose (which is to kill other airplanes). The structural changes that went into the Hellcat’s final design (e.g. reducing drag by changing the engine cowling or improving the spring tab ailerons to reduce roll stick force during combat maneuvers) made sense for what we want out of it, and there were some changes that we decided that just weren’t practical for the time (e.g. adding more cannons).

So, there you have it! That’s really why I thought to title the article as such. I know people can argue that the Hellcat should have came out earlier and the Wildcat was a sh*t (Not technically true, it’s better than what people generally give it credit for) and my plane-fu is the best and yours is a sh*t and so on, but I think given the outcome of the war we can say with certainty that the Hellcat appeared at a time in which it was appropriate.

If it had come out earlier, it would have been a different plane. Some of the specs of the Hellcat as we know wouldn’t have been possible unless you started changing events in say, 1934 or 1936.

For that matter, for a plane to get off the pages, enter production, get modified based on wartime experience (so yes, “re”-design), and enter combat in less than two years and still having produced the Navy’s largest crop of aces and having the biggest kill counts in the Navy?

Yeah, like I said, definitely the right plane at the right time.

PS. Fun fact. Did you know that the Hellcat holds the record for most fighter aircraft produced by a single factory? Yeah. With the exception of a few early ones and the prototypes, one single factory made all twelve thousand of those.

Now, you might be wondering. How exactly is STEC innovating? If the shipgirls’ planes tend to be their historical counterparts, doesn’t this mean that “development” is more or less set in stone? That’s to say, if the fairies can get a Buffalo, the next airframe is probably gonna be the Wildcat, so on and so forth.

As you know, the answer is always a “yes, but…” with these sorts of questions. I think the best way to explain things is basically this. In the same way as a shipgirl’s “ship” class is determined based on whether or not they match up to their real-life counterparts, fairy aircraft are the same thing.

Basically, as you’ve seen in some of our other pieces, there are some fairies that just likes to build stuff. Unsupervised, the things they build tend to be … wonky. I’ve personally seen literal flight-capable potatoes (Solanum tuberosum, as in, the things we eat) coming out the workshops, to say nothing of the inefficient and half-complete items or stuff that flies for a few hundred meters before crashing.

So, part of the job of shipgirls like Cusk (and by extension, Mike and co.) is to make sure that whatever the fairies produce are up to standard. So when you read a STEC report that says, so and so many planes produced, these have been rigorously tested and quality controlled to “count” as that plane based on known specs (for both fairy and of course, their “real-life“ counterpart. I mean that’s how we assign definitions to these things).

In a process we don’t quite understand yet, fairies get smarter and better at doing things the more of them are around. Part of the reason why STEC ends up concentrating everything in Avalon is to capitalize on this advantage. Left on her own, a lone carrier girl’s fairies may be able to carry out rudimentary repairs and sustain replenishment at a very slow rate, but in actual wartime conditions it wouldn’t be enough.

However, the typical configurations of air groups in which we’re familiar with aren’t the only things that the fairies make. If you ever come down there, you’ll find a literal flying circus (at least in the research division – production division is very by-the-books and very good at pumping out stuff that they’ve figured out how to make) of all sorts of items, to say nothing of the random assortment of fairies, planes, and equipment that appears out of the blue on occasions.

So, what STEC’s job is (in my opinion) is to give the fairies some direction, and for STEC to figure out what sort of things STEC needs to fight the Abyssals. Makes sense? The stuff that’s good (e.g. the SBD) we want more of, and there’s plenty of cases where we’d want to see if we can put historical prototypes to “work,” or even come up with our own airframes entirely.

So, how exactly do Abyssal air units function? In other words, what sort of plane would a STEC-Hellcat be against a hypothetical Abyssal-Zero?

Ironically, from what we’ve encountered so far and based on our records, Abyssal aerial assets – the ones that pose threat to aircraft, anyways – are very similar to the perception of the Zero. That’s to say, they’re insanely heavily armed and jaw-droppingly maneuverable. If Abyssal fighter formations reach your attacker aircraft, it doesn’t matter how good the fighter escorts on our sides are, we’re going to lose a lot of those attacking planes.

Similar to what we know of the Abyssals, they’re some sort of biological-mechnical “monstrosity.” There is no “pilot” equivalent from what we can see, and those bladed-looking wings can actually be used for ramming (though we suspect that’s mostly against a conventional opponent). In battle some (but not all) emit a screeching noise, though we are uncertain if this is meant to be communication or if it’s a battlecry designed to intimidate. While it flies like an airplane, its wings are not fixed in place and can be utilized to generate additional force.

What’s their weakness? Well, one, they’re about as well-armored as, well, me-minus-the-whole-being-a-shipgirl-business. Two, unlike the Zero, they cannot climb well, nor can they really accelerate. This, coupled with three (which is to say that their “guns” run out of ammo relatively quickly), means that if a fairy pilot survives the opening engagement and is confident that the Abyssal’s out of ammo, simply running (I’ve heard the term “kiting” used by some of the carrier girls) and forcing an engagement on more favorable terms could work well.

Thus, the crafty commanders can already see sort of aircraft is likely to do well against something like this, no?

Here’s another thing that STEC’s secretly working on.

Initially, it appears that the Abyssals warp their units into the deep ocean, and have them surface from there.

Mike thought differently. He thought that if the Abyssals have flying units, then it necessitates that they have another method of deployment. After all, these Abyssal “planes” can’t exactly dive underwater (though the prospects of that has certainly been brought up and we’re making the appropriate preparations. Tambor’s toy might end up being y’know, standard issue in the future), and if the Abyssals can “warp” into the ocean, then there’s no reason for them to not be able to “warp” into the air.

He was soon proven to be correct, and now we know that the Abyssals can also “warp” units in the atmosphere, where they “drop” onto a location.

So, towards that end, Mike asked us, what do you think of intercepting the Abyssals as they’re coming in? Why not hit the bastards as they’re hitting the field?

At the time, we didn’t think it was possible, since the amount of aircraft needed to cover an area would be too great, and the window of opportunity too small.

Then, of course, MERLIN went up. All of a sudden, we now have a good idea as to when the Abyssals might show up, and where. So, now, we’re thinking along the lines of true interceptor aircraft as one of many possible ways to counter them, particularly as we now know that one particular type of (large) Abyssal are meant to launch their attack the instant it materializes in the air.

The stuff Cusk’s working on? It’s pretty neat. That’s all I can say.

(Now, here’s a strictly out-of-universe comment, directly from Morgane. It is possible for fairies to innovate and create completely new aircraft. However, because Pacific’s roots are in, well, World War II-era shipgirls, from an author’s perspective I want to keep it “grounded” in reality. You’ll see very, very rare or obscure aircraft or designs making an appearance if need be, but to me, I think it’s more interesting (mentally and visually) to create using items that are iconic.

Or, in other words, if in some parallel universe we were doing “tonk” girls rather than “bote” girls, the ones taking center stage would be the Sherman and T34 and Pz. 4, rather than Sturmtiger and T30 and Object–Number-Stalinium. Make sense?)